The All-Time Great Bantamweights: No 3: Pete Herman

3. Pete Herman 101-31-13 (20 KOs)

Back we go to the age of newspaper decisions and fighters duking it out a couple of times every month, where versatility was king and the ring offered no favours to chumps.

To be a top fighter in the early part of the 20th Century there was no hiding place. You had to fight the best around, and you had to fight them regularly.

Pete Herman was one of these fighters. That he achieved what he did in one of the most talent-packed eras for little men supports his case for a ranking this high.

No one came through this period of boxing history unscathed. Even the great lightweight Packey McFarland had the ghost of a phantom loss blotting his record for the best part of a hundred years. That just seemed more likely than someone running the gauntlet without getting their head taken off at some stage. It was that tough an era.

Herman took his digs, but his survival instincts were great: he was stopped just once in over 150 fights. He survived some of the more monstrous 8-stone-six fighters despite a dearth of power to hold them off.

He wasn’t perfect - if he was he’d have topped this list with ease. He walked out the ring a champion nine times but was deliberately poor at times, just because he could afford to be. But it’s the high points of Herman’s bantamweight run that see him afforded such a high ranking. To understand why he was so darn great you have to understand who he was fighting.

Kid Williams: World Bantamweight Champion

Herman was a shoe shine boy who read fight reports in the ‘Police Gazette’, dreaming one day of being as much a champ as the fighters he read of. Turning pro aged aged 16 and fighting good men immediately, he was not a fighter who peaked early. Without the structured amateur system we see today, most boys fought for nickels and learned on the job.

Kid Williams taught lessons in pain and suffering. He was an animal, so much so that the pressmen labelled him ‘Wolf Boy’ and ‘Tiger’. A beastly aggressor who was not hard to hit but hard to hurt and impossible to dissuade, Herman first got in his lane exactly three weeks after Williams had unified the world title by bludgeoning the great Johnny Coulon in three rounds. The Baltimore ‘Wolf Boy’ was at the peak of his powers and Herman found this out the hard way.

Still young and somewhat of a local attraction in New Orleans, Herman was still filling out at the then-bantamweight limit of 116lbs. Sure, he’d fought no less than 30 times in his two years in the game, but this was still considered the ledger of a novice in these rough ’n’ tumble times. An out of town report wondered aloud why recently-minted champ Williams was fighting the "comparatively unknown" Herman.

Kid Williams, ranked 6th on The Fight Site list of all-time great bantamweights

The difference in experience showed. When Kid Williams rolled into town he was already a legend after smashing Johnny Coulon to bits and had beaten the world’s best at bantam many times over.

Still, Herman gave a good account of himself. Winning a single round against this version of Williams was as good as it got, and that’s about all the reports gave Herman. The local ‘New Orleans Times Picayune’ called Williams, “the 'fightingest' little piece of fighting machinery ever seen in the ring.”

Herman was outgunned from the start. Williams’ digs counted for three of Herman’s such was the power behind them, and he used a canny inside game to outwork the young bantam throughout.

But there were positives for Herman to take from the fight. He lasted the ten-round duration (more experienced bantams had not managed that against Williams) and he showed guile and toughness to fire back when Williams got close.

The ‘Picayune’ again:

"How Herman stood up under the heavy fire which Williams directed at his short ribs and stomach was a matter which stumped many of Pete’s loyal admirers, who were near the ring and who plainly could see just how terrific were the tearing-in rights and lefts. The champion would duck in, take one or two left jabs in the face and then whale away with whichever hand was more convenient. He brought right uppercuts from the floor and apparently buried them to the wrist in Herman’s stomach and yet the plucky little Italian never once flinched from this terrific punishment."Eager to score a knockout over his ambitious challenger, the 'tiger' stretched himself to the limit in the ninth and tenth innings, but he was not equal to the task. Do what he would; send in the most telling wallops, he could not bring the little Italian to the floor, nor even put him on the verge of a knockdown."

So the young Herman was durable, game and had a modicum of skill as a pure boxer, but lacked the poise and experience to handle the ferocious Kid Williams. Even his hometown paper said so.

Williams was a hit wherever he went, but was enough of a draw after this fight in New Orleans that he would return for two world title defences a little over a year later.

Whether the Kid was still the true world’s champ at this point is up for debate. He’d ‘lost’ his title when he was adjudged to have fouled Johnny Ertle with a low blow.

Many writers still saw him as the champ though and he continued to defend his title claim. But his form had started to slip a little when he fought Herman a second time in early 1916.

After Ertle, Williams fought featherweight champ Johnny Kilbane (in what we would call a ‘super fight’ today) and was out-smarted and out-fought. He then lost a newspaper decision to Joe ‘Louisiana’ Biderberg, a tough bantam who fought all comers.

Usually you wouldn’t put too much stock in a newspaper decision loss. Ostensibly agreed-upon draws unless a knockout occurs, fighters often entered such fights with their purses guaranteed and as a result often did the bare minimum to survive, or merely punched enough to avoid being thrown out for not entertaining the punters.

For Kid Williams, though, the result is informative. From what we know of him, he overwhelmed everyone he fought during this period, so some publications seeing him the loser against ‘Louisiana’ might suggest he wasn’t at his best. Mind you, everyone is allowed an off-night, especially when they had the schedule of the ‘Tiger’ and 20 rounds separated the men from the boys in those days.

Against Frankie Burns, 20 rounds were not enough for either man. No surprise when you consider just how good these two were.

Burns had beaten Herman (more on that later) and before and after his ‘world’ title fight with Williams would build a resume that was as fine as anyone in this top ten. He wasn’t far off making the cut, and he wasn’t far off beating Kid Williams in a bout described as one of the best ever seen in New Orleans. There was not a minute of the sixty fought that wasn’t entertaining according to one report.

Burns had the better of the early going. Featherweight champ Johnny Kilbane - who had beaten both men - fancied the Jersey boy to win the whole thing. “From the start and during the entire first half of the bout it seemed that Burns would win in a walk," said the 'Times-Picayune', indication that Kilbane’s prediction was not unfounded.

By the end of the fight some observers felt that Williams was hard done by when a draw was announced, given the ferocity of his effort late in the fight.

Williams’ showing was a surprise to even his most ardent admirers. He demonstrated that he was a real champion. Of a most remarkable physique, and in the pink of condition, it took more than the punches of a Burns to weaken his mighty little frame, and when he had his opponent past the stages of the excellent form in which he was at the beginning, he brought to bear his heavy artillery, trained it on the midsection and hammered away.

It was a truly gruelling fight. Given his usual late-round effort and the early struggle he had, Williams didn’t fight for two months (semi-retirement by his usual standards) and when he did it was in New Orleans again. He must’ve liked the scenery.

Herman was better prepared second time around; he’d had 17 fights since he was whipped by Williams, winning 13 of them, and had markedly improved. But he still had some shortcomings.

Giuseppe Di Melfi, or ‘Young Zulu Kid’

In beating respected flyweight Young Zulu Kid, the press alighted on some of these stylistic foibles:

"Zulu looked like a tiny kid about ten years old and though he kept trying all the time that they were in the ring, it was plain from the first round that he was no match for the local boy if the latter wished to go out and do his best. And yet, Herman, it appeared, was not up to his best last night and as a result, the little Brooklyn whirlwind was able in some of the rounds to out-box and out-fight Herman. But in the long run Herman won. He won by fighting in flashes, but the flashes were bright enough to give him a big margin the better of it."

Herman’s tendency to take rounds off and fight to the level of his opposition would see him dogged by critics for the rest of his career. But when he needed to step it up he would, as evidenced in his rematch with Williams.

The big question before the contest was whether Herman could sustain his effort for the long haul. Williams was a champion who preferred a long mill, one who turned the wick up as the minutes ticked by.

Those who put forth this question agreed that Williams had Herman well beat first time round, but also that Herman was a mere novice then and perhaps overlooked now as a potential supplanter to the throne.

The ‘Times-Picayune’ described him as:

"Pete Herman, the local youngster, who has done all that was asked of him in recent months and who has shown so much class that he is thought to have a very good chance of relieving Williams of the bantamweight crown. If Herman were meeting Johnnie (sic) Ertle tonight, the chances are that the local boy would be a favorite over Ertle."

Kid Williams had convinced anyone that considered his loss to Ertle a legitimate wresting of his crown that they were incorrect based on his effort against Burns. There had been murmurs beforehand that perhaps he was a ‘cheese’ champ after all, but his late rounds surge had shown he was still the bantam king.

After the fight, he was a "sore and badly mussed up title holder" as Herman put heavy leather on him throughout, having the iron-chinned battler on "queer street" multiple times.

This is not to suggest that the fight was not competitive. After 20 fast rounds a draw was rendered by the referee, and the press row unanimously agreed. Fans in attendance felt Herman deserved the decision based on winning his rounds in clearer fashion than Williams did, but on a round-by-round basis a draw was given and was fair.

As in their first meeting. Herman had to summon all of his strength when the wind was blown out of him, and Williams came on strong whenever he was stung in return. But Herman showed a few things that clearly demonstrated not only that he had improved, but also that he was the coming man.

Flashback to Williams’ draw with Burns; he was unstoppable in the later rounds (as he always was) and laid it on thick, so much so that some felt he deserved to win the bout outright despite a slow start.

Then see this description of the 20th and final round of Williams-Herman II:

"Herman tore in, rushing the champion to the ropes. Williams put two hard rights to the kidneys and Herman straightened him with a left hook. Herman rocked him with a left hook to the jaw. Williams landed a left hook to the wind. Herman staggered him with a left hook and tore after him, forcing him to the ropes. It was Herman’s round."

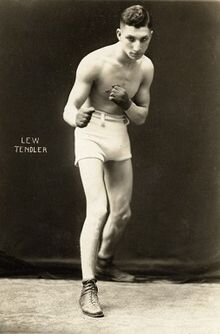

The arguable all-time great Lew Tendler

It should have been Herman’s coming out party. Yet later in the month he dropped a decision to future lightweight contender Lew Tendler (out-jabbed and beaten up over six) then drew over 15 rounds with Frankie Brown in Baltimore.

You come across many excuses when reading post-fight comments after losses, but Herman did have some kind of ailment troubling him as he received surgery after the Brown fight and sat out the next few months.

While Herman sat, Brown got to work. Aiming for a title fight with Kid Williams, he rattled off wins against ‘Louisiana’, Al Shubert and Benny Kauffman, all notable fighters.

It was no accident that Herman’s first fight back was a rematch with Brown. Herman’s manager felt he was fully recovered from the surgery, and wanted to prove the draw a fluke. It was fought at the bantam limit of 118lbs, with Herman wanting to get back on track and Brown hoping to keep his scrap with Williams a certainty.

Brown was the aggressor, outworking Herman for much of the fight. The next day report from the local paper credits Herman for getting his licks in, but it took "a desperate rally in which he literally smothered Brown beneath a fusilade of swings, uppercuts and hooks’ in the 13th to ensure victory."

Herman was not yet at his absolute best, but his prime had begun.

The Italian-American would go 25-0 over the next two years, meeting Kid Williams twice more during that run.

It was 1-0-1 in the series going into the rubber match (again contested for Williams’ world title claim). The ‘Wolf Boy’ had done nothing but win since his draw with Herman, going 12-0 (3 KOs), and the high regard he was held in saw him a clear favourite to beat Herman again.

In a first for the series, Williams hit the deck, a Herman left hook cracking him in the sixth. But the champ was up quickly and followed up with the body assault he’d perfected over the years.

By the tenth, Herman was battered, bloodied, and to one ringside reporter looked like he was on his way out. But right at the end of the 11th round he dropped Williams with a right cross and was right back in it.

It was a violent encounter; Herman almost lifted off the ground from body shots, sharp counters knocking Williams around when the challenger got his timing down. Herman won the 20th round as he had in their tie, hurting Williams with right uppercuts, only this time the champ fought back some as well.

The ‘Times-Picayune’ felt the champ had done enough to retain, seeing him win ten rounds to Herman’s six with four even. Given that Herman had been battered and Williams dropped twice, the round-by-round reports support the view of a closely contested bout. Again, Herman was chastised for being too timid at times and not following up his successes with a sustained attack, but he’d landed many clean punches and out-jabbed the Baltimore tough.

Even given the closeness of the contest, the locals were stunned when Herman had his hand raised. First, because they felt Williams had done enough, and then because the local boy had won the world title!

Herman and Williams would meet again, a no-decision over six which Herman won. Another tight one, some felt a draw would be fair.

But Williams never got another shot at the title. Herman was the world champ, and with that he had a target on his back.

Frankie Burns: The Boxer

Considering that Herman survived the horrendous body attack of Kid Williams, you would be forgiven for assuming he was unstoppable.

Not quite. For in his pre-title years he was stopped by one Frankie Burns of Jersey City.

Herman was not yet in his prime, but he was hardly a debutant either; he counted Johnny Rosner, Young Sinnett and Eddie Campi among the men he’d bested, a decent bunch for sure.

Burns chewed him up and spat him out like he was a nobody.

Herman was "outclassed" according to the next day reports, and he took a worse beating off Burns than he had in his first bout with Williams. Herman had no defensive answer for Burns, who beat a crescendo into his midriff which reached its climax in the 12th round. Herman could do nothing but hang on for dear life.

The sponge was thrown in before the 13th could start, apparently on the young fighter's say-so, though he tried to save face afterward, claiming it against his wishes.

Burns was a marvel, and in fact his performance against Herman prompted the ‘Times-Picayune’ to compare his cleverness in the ring to that of Mike Gibbons, then lauded as one of the most scientific fighters in the world.

"It was simply a master against an inexperienced youngster," they said. "Burns outclassed the local Italian at every department of the game."

Herman regrouped, of course, and through his battles with Kid Williams would become world champion.

Burns had already failed thrice in his attempts to gain recognition as the world’s best bantam; one loss and one draw against Johnny Coulon, and the 20-round tie with Williams.

The day after Herman won his own 20-round bout with the legendary bantam, Frankie Burns offered him $6,000 for a title fight.

It would be ten months before Burns would get his shot, but you couldn’t accuse Herman of resting on his laurels as the new champ.

He beat good contenders; the confusingly named Pekin Kid Herman for one, a hard-punching New York youngster called Joe Lynch for another, and found time to also dust former champ Johnny Coulon in three rounds as well. Although he had yet to make an official defence of his title in 14 bouts since winning it, it would have been snatched from him if he’d been knocked out in the bouts that he and his opponent weighed within the bantam poundage.

Burns had been no less prolific, and since his last world title fight at the tail end of 1915, he had posted an astonishing 30-1-2 record. Jackie Sharkey (three times), Memphis Pal Moore (2-0-1), Joe Lynch, Patsy Brannigan, Frankie Brown, Young Zulu Kid (KO4) and other useful fighters all came up short against him. Burns was in the best form of his life.

The pre-fight analysis measured both men up as such; Herman had the edge in speed and footwork; Burns had the edge in power and body punching; Herman had the more streamlined physique; Burns was stronger; Herman had the better engine; they were equals in terms of toughness.

Given he had smashed Herman with ease before, Burns was right to be confident, telling The 'Times-Picayune':

"There are two or three bantamweights I rate as high as Herman. Unless I get the greatest surprise of my life, I will have no trouble, though it may take me three or four rounds to figure him out. I couldn’t let a youngster like Herman trim me."

Given how respected Burns was at this point, it was a great surprise to all involved when Herman trounced him. He "outfought and out-classed [Burns] in practically every round."

Given how the younger Herman’s defensive radar had been thrown off completely by the shifty, experienced Burns in their first meeting, the fact he displayed "remarkable guarding against Burns’ hardest blows" and counter-punched Burns all he way showed how far he had come. The New Jersey man had winded Herman with body shots a few years earlier, yet this time Herman caught them on his elbows. Burns had been the ring general in their first fight, yet Herman schooled him in the finer points of boxing this time.

Burns felt sure he had the beating of Herman beforehand. As soon as Herman had his hand raised he went over to congratulate him, telling Herman, "Pete, you’re the greatest bantamweight I ever have met, and you beat me fairly, squarely and decisively."

Burns would know; he’d fought all of ‘em.

Herman was then called up for World War One - taking part in exhibitions to entertain the troops - but he continued to fight sporadically as well.

However his reputation would become tainted over the next few years. He went from being the best bantam Burns had ever met, to a ‘cheese champ’ who would for a time lose as many as he won.

Joe Lynch: The Puncher

Newspaper decision bouts are hard to assess. For every local paper that rules a fighter to have won, there is another that sees the fight a different way. If the ebb and flow is markedly similar in the separate pieces you can put the puzzle together and try and figure out whether a ‘loss’ is really so.

The fact is that Herman lost a lot of newspaper decisions during his prime, and the public perception of him was disparate as a result.

The 18 August 1919 edition of The Anaconda Standard summed up their stance on 'no-decision' bouts thus:

"A 'no-decision' or a newspaper decision boxing match is positively meaningless. In the first place there is no incentive for the fighters when the decision is left to the so-called 'popular' verdict. Each man claims to have the majority with him. Each, in his record, has a 'no decision' opposite the match and the date, though each claims to have been the victor. In exactly the same way is incentive to win lacking were the boxers know they are to receive a 'draw' verdict provided both are on their feet at the finish."

This seems to be the approach Herman took. His 1919 bout with ‘Little’ Jackie Sharkey - a tremendous bantam it must be said - saw him do very little until warned by the referee for inactivity. A quick burst of punches would follow to shut the official up, then Herman would go back to stalling. Sharkey took the newspaper decision, Herman kept his belt. The 'Milwaukee Journal' wrote that "both of them left the ring fresher than after a stiff gym work-out".

Herman detractors pointed to the fact he refused to fight these excellent bantams over the championship distance; with an official decision putting his title at risk, it would force a greater effort from both men, and Herman seemed unwilling to exert himself.

The ‘Trenton Evening Times’ wrote of Herman in glittering terms before he boxed there in the midst of this poor run of results:

"Pete goes here and there, taking on all boys that are trotted out to him, and it is seldom that he is the loser. However, he is often given the worst of the newspaper decisions, but this does not effect him in the least. He takes the bitter with the sweet, for he realizes that a champion is always on the short end with the crowd."

Others felt Herman was in fact a weak champion and was hiding behind the shorter distance.

Even his local pressmen were skeptical of his championships credentials. The ‘Times-Picayune’ wrote that although the likes of Jack Dempsey, Mike O’Dowd and Benny Leonard had proven themselves against the best fighters around, Herman "can be classed with none of these", and "the regularity with which he has been defeated in barnstorming tours cause his latter-day acquaintances to believe he is a cheese champion".

The ‘Anaconda Standard’ agreed:

"It is getting to be the regular thing for a fighter to quit boxing anyone but 'easy ones' after they cop the championship honors. Pete Herman, the bantamweight champ has met none but third raters since he held the title. Such battlers as Joe Lynch, Pal Moore, Jack Sharkey and Frankie Brown are off his calling list entirely."

Herman, of course, had fought all of these men before. He was 1-0-1 with Brown; 0-2 with Memphis Pal Moore (both newspaper decisions); 2-2 with Sharkey (at the time the ‘Anaconda Standard’ article was published); and 2-1 with Joe Lynch (all bouts ten rounds or less). He may have not fought these men with the title officially on the line, or rather banked on his ability to survive until the final bell, but he did not avoid them entirely.

His second bout with Memphis Pal Moore followed much of the same pattern as his bout with Sharkey. Moore - one of the greatest bantamweights of all time - put forth a concerted effort. Herman attacked briefly in the fifth round, but other than that was completely outworked. Neither man was in much danger throughout, but most in attendance felt Moore was a worthy winner.

By the end of 1920 Herman had been backed into a corner; there was a contender so good he could not be denied.

Joe Lynch was a demon from Hell’s Kitchen, one of the toughest bantams around. Built like a puncher - tall, lithe and long-limbed - Lynch hurt top-class fighters with his sturdy right hand, and blended his aggression with a well-honed boxing game. He had been on a good run in the few years leading up to his title challenge, beating the likes of Memphis Pal Moore, Tommy Noble, Frankie Mason, ‘Louisiana’, Charles Ledoux and future bantam champ Abe Goldstein.

He even did the unthinkable.

The Olympia in Philadelphia played host to one of the more savage displays in bantamweight history, when Lynch obliterated former champ Kid Williams in four rounds. A right hand dropped Williams in the third, then Lynch completely smothered him with punches. It was evident that "Williams didn’t have a chance", according to The 'Philadelphia Inquirer', and he was rescued by his manager to save him from any further punishment.

Lynch was just as deadly leading up to his title fight with Herman. Just look at his activity in the final months of 1920; Lynch knocked out Abe Goldstein in November, then beat up Johnny Ritchie, a tough journeyman known for going the distance who had fought every bantam around. These were mere warm-ups for Lynch’s Christmas present: a 15-round contest with fellow New Yorker Jackie Sharkey to decide the next challenger to Herman’s crown.

Sharkey was no puncher, and to the layman his record looks like that of a third-rate journeyman, but he was without exaggeration one of the best little men of the era and described as such in contemporary reports. It’s worth mentioning that if this countdown was extended to 25 fighters, Sharkey would feature. He counted Jimmy Wilde, Memphis Pal Moore and Johnny Solzberg among his best wins, and of course had outworked Pete Herman in no-decision bouts. He was a workhorse who threw a lot of punches, a tough and plucky fighter who had wind and jaw to keep going over any distance.

Lynch wrecked him.

Lynch won the entirety of the 15 rounds, and in the final three minutes, Sharkey was described by The 'Brooklyn Daily Eagle' as "a human derelict, battered and torn, a study in scarlet from his nose to his shoulders". He had been dropped four times, saved in the final round by referee Patsy Haley, a fighter of renown in his own time who knew when a man was done.

Lynch was "built on the greyhound type", and "hooked, jabbed and sent over straight punches that were true to form and were up to the mark of scientific boxing", a quintessential boxer-puncher and impossible for Herman to avoid.

Some papers sided with Lynch, but most felt Herman would be able to up his game now it was required of him.

A 'United Press International' preview of the title fight vindicates the notion of Herman as a "bluffer", a true champion who only put forth a top-notch effort when needed. They wrote:

"As a businessman, Pete Herman, the bantam king, is a real champion. He’s just like Johnny Kilbane. For several years they’ve been allowing the fans to think that they’re about all in. They just win by a shade over a second class man in a no-decision affair. This is one reason why Pete Herman, although rated a ‘cheese champion’, is a seven to five choice over Joe Lynch, considered the best boy of his weight in the country."

New York papers sided with Herman too. His jab and speed were seen to be the deciding factor despite Lynch’s obvious qualities.

In front of 15,000 spectators at Madison Square Garden, Lynch wrested the title from Herman in a tame bout where both men were wary of the firepower coming back at them. Herman only fought hard in the tenth, and at the end of it Lynch was New York’s first bantamweight champion since Terry McGovern two decades earlier, his accurate right hand being the deciding factor.

Herman gave Lynch full credit for the victory;

“The better man won. I wish Joe Lynch the best of luck. He outboxed me.”

Herman didn’t seem too down after losing his title. Although the performance was indicative of his lowly efforts in no-decision bouts, he immediately set sail across the Atlantic.

He had something other than the bantamweight crown on his mind.

Jimmy Wilde: The Greatest Flyweight

There were great bantams in the States, but no little man had more name value than Jimmy Wilde. No one terrorised the lower weights like ‘The Mighty Atom’ did in the 1910s, and it can be argued within reason that the sport has never seen a greater fighter of the poundage. The Welshman was the first unified world flyweight champion, beating the best of Britain, Europe and America whilst not weighing more than today’s strawweight limit.

Such was his skill that he had no qualms fighting bigger men; he had beaten Joe Lynch and Memphis Pal Moore on points, and his one loss above the flyweight limit was a no-decision bout to ‘Little’ Jackie Sharkey, one of those bouts where you picked what you preferred; Wilde’s accuracy, or Sharkey’s work rate. Wilde even stepped up to featherweight to completely destroy British champ Joe Conn.

Respected worldwide, Wilde was a true marvel. Surviving footage of him shows a master boxer and a trap setter, one whose fast hands and unerring sense of distance dumbfounded his opponents. Then he would hammer them. All in all he felled nearly a hundred men, many of them first-raters. Styled as ‘The Ghost With a Hammer In His Hand’, Wilde was hard to hit and hit hard himself. He was regarded as a legend in his own time, a rare distinction.

Such was his reputation that Wilde was favoured by the British press to beat Herman.

‘So abounding is the faith inspired by Jimmy Wilde that one finds it difficult to imagine his defeat, no matter what the character of his opponent may be’, wrote The 'Pall Mall Gazette' on the eve of the showdown.

The same publication credited Herman as the best fighter Wilde had faced up to this point. High praise when you consider the wide range of excellent fighters the little man had beaten.

'Pollux' was the pseudonym of a writer you often see when scouring the British boxing press at this time. A well-reasoned scribe, he felt Wilde would be much too good for the visiting American. He had spoken to friends across the pond and watched Herman in training, and wasn’t too impressed.

"From what I have been told by these friends, and from what I have seen of Herman, I am firmly of the opinion that Wilde will prove victorious tonight at the Albert Hall without a great deal of trouble. I have come to the conclusion that, in spite of his superior weight and alleged greater strength, the speed and hitting power of the Little Welsh Wonder will be found too much for him."

Overall, 'Pollux' gave Wilde the edge in footwork, speed and punching power.

No less a venue than The Royal Albert Hall would be the setting for this battle of tiny titans. Contracted for 20 rounds and 118lbs, Wilde was disappointed to hear that Herman had lost his world title so shortly before their bout. Herman refused to shift an extra pound as well, and it took a coaxing from the Prince of Wales to convince Wilde to fight at all.

The first round started late as a result, but Wilde appeared unperturbed in the ring. He started "briskly enough" and won the first round according to the London newspaper 'Daily Herald', and was winning the second when Herman cracked him with a left and rights, visibly shaking up the smaller man.

The same report credited Herman with "consummate coolness" and that "even against such a master he could hold his own in skill". In the third, Wilde landed effectively. In the fourth, both men were "infinitely clever", with "science and skill reached to a height not seen for a long time in a boxing contest".

Herman had an edge in the fifth, though Wilde landed a series of sharp right hands to his mandible. Herman remained patient, and increased his body attack over the following rounds. Wilde won the sixth clearly though, counteracting Herman’s inside work with clean jabs and generalship.

From there on Herman had much the better of it. Wilde fought well to even up some rounds, but Herman was getting through with aplomb to body and head. In the later rounds, Herman had The Mighty Atom groggy more than once, and flattened him in the 17th with a right hand. Wilde bravely rose to his feet, but the fight was over.

Post-fight, the London press felt the weight was the big difference. It must also be said that Wilde had given up weight before and not been in nearly as much trouble.

Years later, Wilde would claim Herman was a featherweight, that he had refused a further weigh-in, that he didn’t want to fight and was forced to. Contemporary reports say he relented, but that he was in superb form and fighting shape and had tried his best to win. The Associated Press report gave Wilde the first five rounds.

Herman said after the bout:

“Wilde is the greatest boxer that I have ever seen. I was in better condition for this fight than I have ever been in before”.

He needed to be. The extra pound-and-a-half notwithstanding, Herman had done a better job on Wilde than any of his peers.

Including Joe Lynch.

Two-Time Champion

Lynch had started to show some of the spotty form that Herman had as champ. He’d still won more than he lost, but split fights to excellent bantams such as Young Montreal, and lost a newspaper decision to Memphis Pal Moore.

Herman had impressed the English enough that he travelled back to Britain to fight the domestic title holder Jim Higgins. Higgins was a game and aggressive Scotsman, and there was talk of him challenging Lynch for the world title if he beat Herman. This bout is interesting as it is the only filmed bout of the New Orleans man which seems to have survived.

It is doubly interesting because the celluloid proves that Herman was exactly the fighter described in contemporary reports; outworked for much of the bout (but defensively sound) Herman appears to get bored of the exercise in the 11th, whipping in two quick shots to iron Higgins out for the full count.

Frustratingly, Herman failed to make the contracted weight again, half a pound over the bantam limit at the weigh-in.

‘Pollux’ wrote:

"Had he made an attempt (to lose the half pound) on one of the hottest days within memory, Herman would have gained a certain amount of sympathy, but his obstinate attitude in refusing to make an earnest endeavour is anything but the true spirit of the sport."

Weight issues notwithstanding, it would be Herman, not Higgins challenging Lynch. For the rematch, the press favoured the champion, given his hitting power and sound defence. It would be a 15-round title fight, again in Lynch’s Big Apple backyard. Herman’s inability to make the weight comfortably buoyed the confidence of Lynch’s supporters.

Herman & Lynch square off

Yet Herman came in at a trim 116 3/4lbs. Dedicated and driven, the veteran "had the better of it all the way" according to one report. It was a boxing match, with Lynch complaining afterwards he had hurt his right hand early.

Lynch did not disgrace himself, but Herman was said to have won by such a landslide that there was no disputing the decision. The 'Brooklyn Daily Eagle' said not only did Herman win with his clever and quick footwork, but that he was "probably the best in-fighter in the world". Another report said it was "a sensational comeback" and gave Herman 13 rounds, with one for Lynch and the other even.

Herman had honed these skills fighting the absolute best the division had to offer for nearly a decade. He would lose his title in the first defence of his second reign, then Lynch would pick it up again, demonstrating both his class and the importance of Herman having him on his ring record.

So what of Herman, the man once close to being a ‘cheese champ’ rather than an all-time great? Simply put, the best scalps on his record would come close to a spot in the top ten, and in Kid Williams he went 2-1-1 with a true all-time great and a fellow member of this top ten.

"Pete, you’re the greatest bantamweight I ever have met, and you beat me fairly, squarely and decisively."— Frankie Burns

Those that beat him fair and square wouldn’t be far off either; it was simply one of the best bantamweight rosters ever seen. Herman’s inability to beat everyone and his sometimes lacklustre performances need to be taken into account, as do his small amount of legit title defences, but his highs are greater than most on this list, while his lows do not explain away his brilliance.

Even with his defensive style, Herman was a casualty of this era. He later went completely blind, but his greatness should be clear for all to see.

No less a figure than Ray Arcel - arguably the greatest boxing trainer of all time - ranked Herman among the best 12 fighters he had ever seen. The other 11 included Roberto Duran, ‘Sugar’ Ray Robinson, Harry Greb and Joe Louis.

This is the crowd Herman deserves to be in, so its only natural that he finds himself up in third place on this list.

Two more to go. It’s only monsters from here on out...