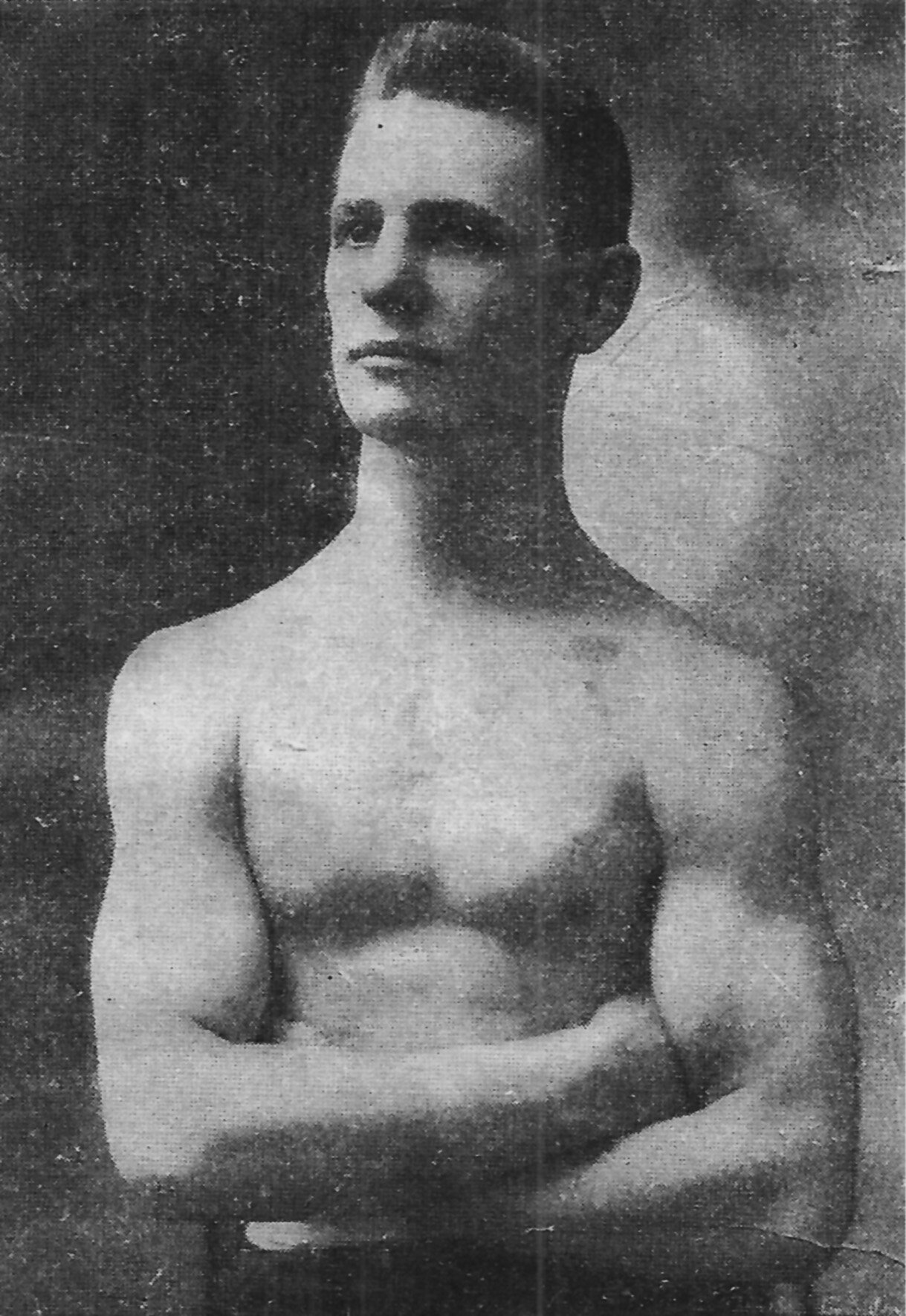

The All-Time Great Bantamweights: No 2: Terry McGovern

2. Terry McGovern 65-6-7 (44 KOs)

The early days of gloved boxing was the Wild West era, where Wyatt Earp refereed a prizefight and the sport was still outlawed in many states.

The leading gunslinger of these years did not draw his irons in the wild west, but the east.

Irish-American Terry McGovern, Brooklynite, terror of every weight class from bantamweight to lightweight, ruled boxing at the turn of the 20th century. His reign was not a lengthy one, but his ring record is littered with bodies, the lack of surviving footage sparing our desensitised 21st-century eyes from possibly the most violent man to ever step foot in the ring.

It was a time of precocious fencers and unhinged madmen. McGovern fought them all.

A Natural Fighter

Before he would be given the moniker of ‘Terrible’, young Terry McGovern first had to find his way into the prize ring. He donned gloves and traded punches out of necessity. Fatherless at ten and having to support his mother and young siblings, McGovern did not go to school, instead working as a gardener. A report from ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ written at the height of McGovern’s prime in 1899, looked back to his start in the prize ring, which seemed to be a hunt for more money and a better life for his family than McGovern could earn elsewhere:

"Two years ago a sturdy, modest little fellow, with hands as callous as an elephant’s hide, walked into Schiellein’s Assembly Rooms in New York, where an amateur boxing tournament was billed to take place, and informed the managers of the affair that he wished to try for a prize in the bantam weight class. He came unheralded, unsought, and unknown. There was nothing about his general appearance which struck the managers as unusual, except that his fame was what we commonly term sturdy. Whether boxing is a lowly calling or not does not detract one whit from the credit that is due to the young fellow, who was Terry McGovern. That was the name of the boy - the same lad who won a ten dollar prize in the aforesaid tournament by knocking out four other aspirants. In two short years this mere boy has leaped from obscurity into the lime light of fame and fortune."

McGovern did fight in an amateur tournament even after his first pro bout, but if the exact details of his start in the game are lost to history or at best hidden below the surface, the first known bout for McGovern was a perfect indication of the unbridled violence to come. Seventeen years old, 110lbs, little Terry McGovern fought fellow novice Johnny Snee. Nothing is known of Snee, other than his profile being a bloody mess when McGovern got his mitts on him. In what was a one-sided routing, McGovern’s eagerness to dish out violence was also his downfall, thrown out for dirty work in the third round when trying to put his man to sleep. A few weeks later McGovern went ten rounds against an opponent who came in overweight. Terry spotted him the pounds and beat him up anyway. A sign of things to come.

McGovern being disqualified for sheer savagery is the only time he lost in his first four years in the ring. His record in this time? 55-2-4, a champion at two weights and a force of nature so hostile he smashed the best lightweights in the world with as much ease as he did the bantams.

It’s those bantamweights that are of most concern to us here. And as we’ll see, also the featherweights.

American Bantam

All reports of McGovern’s early bouts sing from the same hymn sheet. McGovern’s song was not that of a graceful choir, but of pounding heavy metal; a marauding, non-stop pressure fighter who had only one intention - to knock his opponent out.

Tommy Sullivan

The only man to push McGovern close in his early fights was undefeated Tommy Sullivan. Described as ‘bantams’ but fought at the modern flyweight limit, this bout does nothing for McGovern’s ranking here but it is insightful all the same, as Sullivan would in time would become world featherweight champion, destroying Abe Attell in five rounds. A draw was as good as anyone managed against McGovern, lest he get himself disqualified for rough housing.

Draws and disqualifications featured in McGovern’s first rivalry. Philadelphia native Tim Callahan was a shifty type, a talented boxer, and in a trilogy fought over four months in 1898, McGovern’s burgeoning talent and unparalleled ferocity can be accurately traced.

McGovern lost the first, although as previously stated he was never legitimately beaten in this time. Fought at 114lbs - bantamweights in this era but below the threshold designated for this list - McGovern got much the better of the fight but was warned frequently for striking Callahan in the clinch.

The rules called for one arm to be free in the clinch, so McGovern’s tactics were likely above board. But he continued with the tactic and was thrown out in the 11th, Callahan victor by disqualification.

This is where reports differ on their interpretation of what transpired; ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ said McGovern "seemed to lose his head" and "repeated the offense".

‘The New York Press’ saw it differently. McGovern had been "fighting fiercely in short range" when the referee stopped the bout. Contrary to the ‘Daily Eagle’ report, when McGovern was thrown out he had not been bending the rules; McGovern was punching freely with both hands. The same paper said that McGovern had "got the worst of a bad decision".

Not that Callahan was a mediocre fighter, something he proved when they clashed again a few months later. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ was impressed with Callahan, calling him a "quick, shifty and hard fighter" who knew "all the tricks of the trade". He must have been good as he extended McGovern the full 15 at 115lbs, and the bout was declared a draw.

Callahan had been on a decent run since coming to New York. Whatever we make of his first bout with McGovern, he was skilled enough to survive him for 15 rounds afterward, and had also fought solid contender George Munroe twice before his third meeting with McGovern.

Munroe would mix in top class for much of his career, and had fought McGovern thrice in 1898 as well, disqualified once, going 20 rounds to a draw in another, and to no surprise also being knocked out.

Callahan was not the puncher McGovern was, but in his first fight with Munroe he gave "one of the prettiest exhibitions of scientific boxing seen", and the crowd - albeit a small one - were aghast when a draw was announced after 20 rounds. Callahan was a defensive stylist, who ducked punches well and had ‘fast foot work’. Callahan was not just a cutie though; in the late rounds he came forward and ‘administered severe punishment’ to Munroe. In their October rematch, Callahan won a rightful 20-round decision, and set himself up well for another go with McGovern.

McGovern was 0-1-1 with Callahan at this point, even if the loss was an unjust call. The third bout showed McGovern as Callahan’s superior. The weights are not known at this point and may never be, but seeing as they had previously fought at the (then) bantam limit of 115lbs it is likely that they met there again, or perhaps a pound above or below.

What is clear to see is the beating Callahan suffered at McGovern’s brick fists. Also apparent is McGovern’s technical mastery of Callahan.

Shifty Tim Callahan

Callahan did all the leading early on, but McGovern "cleverly blocked" his punches. It was a fast competitive fight from start to finish, and in the eighth round McGovern found the measure of his man and started walking him down. In the ninth McGovern had Callahan groggy from "repeated smashes on the ribs and kidneys". In the tenth and final round, McGovern dropped Callahan twice, the second time from a right hand upstairs set up by a jab to the body. McGovern reads not just as a ferocious pressure fighter but also an intelligent one.

This series is also impressive as Callahan would go on to become a fighter of some repute, beating many first-raters. McGovern stopping him is also an indicator of his class as Callahan would not be knocked out for another decade, then a veteran of at least 140 pro bouts who had seen better days.

After seeing rid of Callahan, McGovern would fight nothing but the best men the lower weights had to offer.

Harry Forbes was perhaps the best of McGovern’s opponents on his run to the championship. A boxer from Chicago, Forbes earned respect from the New York pressmen with his speedy and smart showings in the big apple. He had not been a prizefighter for long, but was credited for his "splendid work" by ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’.

Forbes was good enough that many patrons allegedly lost money on him, for McGovern knocked him out in the 15th round in a "fast and scientific" bout. Forbes would return, with more experience and plaudits to his name. McGovern would be waiting for him.

Austin Rice had drawn with Tim Callahan, ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy, George Munroe, and even the hard-punching Oscar Gardener. After fighting McGovern he would go on to beat George Dixon, Tommy Sullivan, Callahan, and would even fight for the world crown at featherweight. He was a top battler in his day and still in his prime when he signed to fight McGovern.

They fought on New Year's Eve, and McGovern ended an excellent 1898 campaign by stopping Rice. But McGovern’s aggression was nearly his undoing. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ saw McGovern as a consummate ring general, setting Rice up for big right hands which had him sprawling, and although McGovern had issues landing his left early, he also stopped Rice from landing with his own.

Austin Rice

In the 11th, McGovern was dropped, a rare misstep; "he grew careless in his anxiety to win quickly" according to ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ and - although under duress - Rice still had his wits about him to time a right hand to the jaw which sat McGovern down. McGovern rallied, continuing with the clever work he had shown earlier in the bout, and Rice was forced to quit before the 15th round could begin.

McGovern wanted to square up with Jimmy Barry, who held a title claim which was either called ‘Paperweight’ or ‘Bantamweight’, a title he defended anywhere between 105-110lbs, although he had also taken on fighters closer to McGovern’s weight. A fight between Barry and McGovern had been arranged before but never came off, and Barry might have been reluctant to meet the surging New Yorker. He sat out the rest of the year, fighting only once more and retiring undefeated.

McGovern had to be content with Casper Leon, a previous Jimmy Barry challenger. He’d gone 20 rounds with the champ, and was coming off a win over ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy, another excellent contender of the time.

Casper Leon

Leon, an Italian born Gaspare Leoni - and known as the ‘Sicilian Swordfish’ - was a naturally smaller man, a modern flyweight, but he was an experienced fighter who had gone the championship distance and claimed the American bantamweight title. ‘The Sun’ (New York paper) called it "an important bantam weight match". McGovern barely squeezed into the 115lbs limit, perhaps a sign of things to come, but he blasted Leon in 12 rounds; a body assault softening Leon up, a left "on the point of the jaw" flattening him for the count.

‘The New York Evening Telegram’ said that McGovern "so clearly outclassed Leon that no question will be raised for some time about the great superiority of this fiery little chap". The ‘New York Journal and Advertiser’ noted that Leon’s boxing skills had kept him in the fight (with McGovern taking "a good jabbing") but that the larger man had never faltered in his task.

‘The New York Morning Telegraph’ called McGovern "the best 115 pound boxer in the world" and said he "had the fight well in hand from the first tap of the gong to the finish". The same report credited Leon as a "clever Italian" who made "a strong and determined defense, and never flinched till the last". Leon had landed well with jabs and right hands at times, but McGovern "paid no more attention to them than though they had been snowflakes". ‘The New York World’ said that after this knockout McGovern was "the peer of any man of his weight in the world". ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ said that Leon was "one of the cleverest boys in the division" and observed that he took several minutes to recover from the knockout blow. Despite the size difference, this was an impressive win over an accomplished fighter.

McGovern did not rest on these plaudits; he fought in each month from January through July. In March he fought Patsy Haley, a legit bantam who had once fought at 118lbs in a bout billed as being for the ‘world’ title. The gold standard for little men at this point in time - at least in Britain - was the clever Pedlar Palmer. Haley was said to be far below that standard by British writers after his 20-round loss to Will Curley (another promising British bantam) but was said to be "undoubtedly clever" and a "shifty boxer".

So Haley had missed out on a lucrative fight with Palmer, but was still a contender of note. His recent results included draws with Oscar Gardner, Tommy Sullivan and Johnny Ritchie, all world-class fighters.

Fought at 116lbs and scheduled for 25 rounds, McGovern demonstrated his excellence in comparison to his peers. ‘The Daily Eagle’ wrote:

"By knocking out Patsy Haley of Buffalo last night at the Lenox Athletic Club (McGovern) accomplished what Oscar Gardner failed to do in twenty rounds and what took Dave Sullivan twenty-three rounds of the hardest kind of work to do. Haley acknowledged before the exhibition began that he was never in better condition in his life."

The same report said Haley had made "a good showing", and that "his clever foot work saved him several times".

McGovern was not as quick as Haley, but his blows carried more weight and he placed his shots well. McGovern relentlessly pressured Haley, and in the 18th he finished him off with a blistering combination: left to the body, left upstairs, then a "crushing right hook on the jaw" that deemed a count unnecessary. ‘The New York Wold’ said that McGovern "shot his right over and Patsy fell like a log". The same report noted that McGovern had feigned grogginess to try and trick Haley at times, but the Buffalo man was shrewd and did not fall for any of McGovern’s traps. McGovern’s aggressiveness was necessary as Haley tried to box and survive.

In April, McGovern spotted featherweight contender Joe Bernstein around eight pounds. Bernstein was not a big puncher, but his added weight and experience against the best men around meant that McGovern was up against it. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ called McGovern "the hardest hitting man of his weight and inches in the world" prior to the bout.

Bernstein was clever and precise, and shook McGovern up in the fifth with a shot around the ear. McGovern fought back though and "cut loose with a vengeance", Bernstein’s successes being few and far between as the fight progressed. The bigger man’s high guard forced McGovern to target the body, which of course he was comfortable doing. In the final round, McGovern "at last succeeded in getting over his right" and Bernstein staggered to the ropes. Bernstein’s guile saw him through, with McGovern a worthy winner after 25 hard rounds.

Featherweight Joe Bernstein

Men of McGovern’s poundage struggled to withstand his punches.

Although his record shows little in the way of knockouts, Sammy Kelly carried his dig late into the fight and stopped a few notable fighters. Kelly had stopped Austin Rice, gone 20 rounds with Jimmy Barry and in his prior bout had matched Oscar Gardner at 116lbs, fighting gamely before before stopped in 14. His best win was over the excellent Englishman Billy Plimmer back in 1897, Kelly crossing the Atlantic to knock out the Brummy battler in the 20th round in a bout advertised as being for the ‘world’ title at 115lbs.

"Terry McGovern’s ability to hold the bantamweight championship will be tested when he meets Sammy Kelly on Friday night", said ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’. "Kelly has not fought since his memorable battle with Oscar Gardner and has completely recovered from the broken rib he received on that occasion. He says the long rest has been an incalculable benefit to him and he is stronger now than he ever has been."

Sammy Kelly

Kelly had taken interest in McGovern’s previous bouts and considered him an easy out. McGovern showed he was anything but, with Kelly holding on for dear life from the outset, clearly bothered by McGovern’s hits about the wind. Following the usual pattern of his bouts, once his opponent was worried about the shots to the body, he raised his aim, sparking Kelly with a right hand in the fifth round.

"The fight was not that interesting," wrote ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’, "but showed that Terry is a good boy for many others to keep away from."

Billy Barrett was reportedly a former amateur standout, and was in somewhat of a purple patch. Unbeaten in eight fights including wins over Patsy Haley and George Munroe, Barrett had also fought (and lost) to the excellent Harry Forbes, and lasted ten rounds with McGovern when he was still a novice.

McGovern was a novice no more, and Barrett "developed one of the most brilliant streaks of yellow imaginable" and "laid down like a whipped dog" when McGovern landed a strong punch in the tenth. No weights were announced but Barrett usually fought men of McGovern’s size, so this was likely a bantamweight contest.

Chiacago bantam Johnny Ritchie had struggled with some of the best bantams he faced (notably Eddie Sprague and Harry Forbes) but had made some noise with his recent victories, including a ten-round decision win over Patsy Haley. He was one of many excellent operators in the lower weights that fought out of ‘The Windy City’, chief among them Jimmy Barry, whom had defeated Ritchie over six rounds a year prior. Ritchie was game, and was styled as the ‘Western’ bantam champ.

Before the fight, the terms were announced in the ring: 118lbs, for "the bantamweight championship". This is presumably the national title, as it was then announced that the winner would face Pedlar Palmer for the world championship.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ deemed Ritchie a "clever boy", and noted his strong effort in the first two rounds. However, the same publication observed a look of fear just not on Ritchie’s face, but in his work. McGovern installed this fear into his opponents, the certainty of a beating turning competent fighters into cowards.

Johnny Ritchie, Chicago contender

In the first round Ritchie landed good lefts on McGovern’s face and the New Yorker couldn’t land with his own counters, so presumably Ritchie was out-jabbing him. Ritchie was credited for clever parrying of McGovern’s punches. In typical fashion, McGovern rushed Ritchie and started landing first about the gut and then to the face. The Chicago boy looked "amazed at McGovern’s aggressiveness". Ritchie recomposed himself, landing a stiff jab to end the first.

In the second McGovern set about his man, backing him up to the ropes and landing effectively. Ritchie showed cleverness in getting back to a more favourable position, and landed with a one-two that was clean but did little to hold McGovern off. McGovern showed "no respect" for Ritchie’s offense and dropped him near the end of the round. Ritchie was up immediately and clinched his way through the end of the round to survive.

Ritchie should have remained in his corner, for in the third round McGovern annihilated him. The Irish-American did not waste any time feinting or jabbing with Ritchie but simply ran after him, giving him no room to escape lest he climb through the ropes. McGovern was "flushed with excitement", but Ritchie "showed great cleverness" in avoiding some dangerous looking blows.

In close, Ritchie could not handle McGovern, who hit him in the clinch and generally ragged him around the ring. Ritchie tried hard, but he was ready for his bed, a right hand knocking him half asleep and a follow-up left sending him into dreamland.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ summarised McGovern’s devastating power punches thus:

"The blow which accomplished the trick was a left hand hook on the point of the jaw. It was delivered with lightning speed and crushing force. Nothing human could stand before that blow and breathe comfortably, and Ritchie, being made of flesh and blood turned turtle and fell on the floor upon his face."

If this article reads as "and then McGovern knocked this guy out, and this guy out, and then he beat this contender up", it’s because in his prime this is what he did. Consider him a lower weight Mike Tyson; a flame that burnt at its brightest briefly, but in that time scorched anyone who got close to it.

McGovern had battered the best bantams the United States of America could offer up. But there was an majestic boxer in the land of tea and scones who figured to be his biggest test.

The World Bantamweight Champion

"To the intense astonishment of most present, and the consternation of many, the long-looked forward to contest between the renowned Billy Plimmer and Pedlar Palmer, which was decided last night, resulted in complete defeat of the accomplished Birmingham boxer at the hands of the clever Canning Town youth."

Pedlar Palmer, legendary English boxer

Young Londoner Pedlar Palmer was respected before he fought Billy Plimmer, with a win over respected little battler Walter Croot an early highlight of his career. But his complete domination of a fighter who was likely one of the best lower weight fighters in the world marked him as a fighter of not just high quality, but of high stature among the writers of the day.

‘Sporting Life’ was not just astonished at Palmer’s victory, but the way he went about it.

Palmer was not only "quicker and cleverer" than Plimmer - something "that many good judges thought impossible" - but his speed and ring smarts had "not been seen for years".

Plimmer was regarded by some as the ‘champion bantam’ of the world, and had been to the States, gaining respect on the other side of the pond for his four-round decision win over the great George Dixon, then respected as one of the best men in the world regardless of weight and the king of the featherweights. This bout was over a short distance, but still, Plimmer was held in high regard after it. Before and after his fight with Dixon he was generally regarded as one of the smartest fighters in the world.

Billy Plimmer

Palmer however, just 19 years old, dominated Plimmer from the start. In the 14th the Birmingham man was disqualified when his seconds rushed the ring to save him from further punishment, ostensibly a corner stoppage. He’d had enough.

Within a month Palmer had crossed the sea to fight Dixon, one in which he matched Dixon for cleverness but likely got bested in, the fight ruled a draw after six. No shame.

After this Palmer did nothing but win, beating quality fighters from Britain, Ireland and America, among them undefeated Irishman (via Boston) Dave Sullivan (20-round decision) who would go on to win the lineal featherweight title; unbeaten Billy Rotchford from Chicago (DQ in the third round, Palmer looked to be a class above); and Plimmer again (16th round KO, two right hand socks to the jaw flattening the Birmingham man) were other notable victories the Canning Town youth accrued.

American Johnny Murphy, who had been 40 rounds with George Dixon and held the accomplished Ike ‘Spider’ Weir to a draw, was no more successful at combating Palmer’s skill set than anyone else. He was extremely game, but at the end of 20 rounds ‘The Sportsman’ felt Palmer would "reign supreme for many years" as bantam champion.

The National Sporting Club in England recognised Palmer as the world champ at bantam, his claim following him up in weight from the modern flyweight limit to 116lbs. Boxrec has Palmer at 26-0-1 when he traveled to New York to fight McGovern, but it is likely he fought in many more bouts. All reports of the time refer to him as being undefeated. He was 23 years old to McGovern’s 19. Both were undoubtedly in their prime fighting years.

The 16 September 1899 edition of the ‘Illustrated Police Budget’ published a preview of the fight which gives us a better picture of Palmer’s style:

"Two more dissimilar styles in boxing could not possibly be imagined than those employed by Palmer and McGovern. The former is one of the trickiest little fellows that has ever put up a hand. Quick and agile as a cat, he is here, there and everywhere, putting into execution more dodges and expedients than any two ordinary men. He is termed the 'box of tricks', and certainly no name could fit him better. His head work is simply marvellous, and very frequently he has been known not to attempt to defend himself with his arms at all, but to stand up to his opponent and dodge the blows solely by the wonderful rapidity with which he would manipulate his little head piece. His foot-work too, is a perfect study and these two factors, when added to the great ability he is possessed of in the handling of his 'dukes' have made him what he is, a veritable champion."

So for his day, Palmer was a prototypical Nicolino Locche (or for a comparative defensive wizard from his own era, Australian featherweight legend Young Griffo) who would use his supernatural reflexes and fine judging of distance to slip punches effortlessly.

Training reports of Palmer sound like he and his team were ahead of their time: rather than lengthy jogs, short bursts of sprints punctuated his long walks, perhaps to replicate the flurries he would try to land in a 20-round fight. Weights, rope and bag work also made up his regime.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ wrote of McGovern’s meteoric rise, his penchant for knocking contenders stiff, and of his standing as favourite for the upcoming clash. They also noted that Palmer was likely to be his stiffest test:

"Should an opponent clinch then is the time Terry is most dangerous. With both hands working like trip hammers and hitting a blow almost as hard as a lightweights he soon has his opponent so anxious about avoiding further punishment on the body that he leaves the opening for the head, which Terry is always looking for, and then with left or right, as occasion demands, comes the blow which cuts short the timekeeper’s work. In Palmer, however, Terry is to meet the hardest proposition of his career. The English lad knows all the tricks of the game and is a thorough master of all the fine points. He is wonderfully strong and fast on his legs and a past master with the left hand and confidently believes that McGovern will be no harder than some of the men he has already disposed of. Palmer hopes to tire Terry with his rapid foot work and with a good use of his left wear the Brooklyn boy down and finally find the opening for his right."

McGovern saw the bout the same way, but also felt his own cleverness would be a factor:

"Even if Palmer does get the opportunity to land some smart blows on me, I am not even then so certain that they will hit me where they will do much harm, for I have made it a practice to avoid blows by ducking my head and otherwise dodging without using my hands, so as to have them immediately available for the purpose of doing some offensive work at the slightest opportunity. I have managed to attain considerable cleverness in this dodging work and, as a rule, receive the blows on the back of my neck or some such harmless place. As I can hit equally hard with either hand, it makes no difference to me on which side the opening comes or which fist lands the blows."

Despite McGovern’s claims of cleverness, it was seen as a scientific artist of the prize ring versus a savage, a throwback even in these wild, violent years.

The fight was well publicised. As well as lots of column inches being taken up discussing the particulars, both men also refereed bouts on the same card to drum up local interest. Palmer also came out and gave a speech, in which he thanked the Americans for the warm reception he had received.

They would be fighting for a $10,000 purse, an astronomical figure for the time and said to be the biggest purse to date for bantamweights by contemporary sources. This would be around $300,000 today; a large purse for modern bantamweights! They would also get a cut of the receipts from the motion picture, still a big deal in these days.

The crowd in Tuckahoe, New York would have to wait to see how the clash of styles would play out, as the fight was postponed due to rain. Both men had already made weight and started to rehydrate when the decision was made. It was said that McGovern would find it much harder to come back down to the 116lbs championship limit.

The wire report was thus delayed, and the British faithful would have to wait for news of how their boy got on. Some had made the trip over, "with plenty of money to wager" according to New York newspaper ‘The Sun’. These would be very well off fans of pugilism; the majority would have to wait for the result to be printed in the papers.

Palmer’s message to his fans back home was relayed in the ‘Illustrated Police Budget’:

"They tell me that McGovern is a bit mustard: but they must not forget that I am also a trifle ‘Coleman’s’ when I am on the job, and you can bet I am going for it this time. So that if I am whacked it will be by a corking good lad."

Palmer was indeed whacked, in what remains to this day one of the more astounding results in boxing history.

McGovern came down flanked by his seconds, one holding the Stars & Stripes aloft, the other the Irish tricolour. Palmer proudly displayed a Union Jack. The downpour of the day before was gone, and the sun made it a beautiful day according to more than one source.

Pedlar Palmer’s day was about to be darkened.

Palmer and McGovern, as they might have looked squaring up

The first round was almost cut short by an over enthusiastic timekeeper halfway through. McGovern didn’t need the rest of it.

"McGovern outclassed Palmer" read the ‘New York World’ report. "The fight was so one-sided that it is almost impossible to see how Palmer, though the best boy in England, ever could have expected to win. McGovern was quicker, stronger, and by far the more intelligent of the two."

And clearly more savage. Palmer was first affected by McGovern’s feared body punching. He went down early, one report makes it seem innocuous enough, perhaps a case of tangled feet, perhaps a punch-cum-shove. But when he wasn’t landing hard, McGovern skipped in and out of range. The same ‘World’ report said that McGovern was "the equal of Jim Corbett in clever footwork, getting in and out of hitting distance like magic".

First blood to the brawler then; wholly capable of jousting with the supposed master boxer.

McGovern used those slips and feints he described before the fight to get close to the Londoner, then he ripped left and rights to the ribs. Palmer was in a lot of discomfort.

When the timekeeper first rang the bell (he accidentally dropped his hammer) both boys went back to their corners. McGovern was smiling. Palmer could be forgiven for thinking the round was over given that it must have seemed like an eternity.

Within five seconds the referee had noticed the time keeper's mistake and rushed both boys back to centre ring. Palmer tried to fight back, landing a few short blows to McGovern’s own ribs, but saw "most of them go wild and only strike the boy’s shoulder". McGovern’s underrated defence again.

Palmer went for broke, swinging a big right hand at McGovern, who slipped it and slammed a short left hook into the champion's jaw. Palmer went down in a heap, but jumped up at the count of three, rushing McGovern, trying anything to keep his undefeated record intact.

"He hears nothing, sees nothing but that mocking grin on the brown face of the Brooklyn lad. In he dashes, caution thrown to the winds, both hands flying in swings, ducking his head curiously and awkwardly from side to side. Terry blocks him and waits his chance."

Palmer was desperate. McGovern capitalised; a left hook to the body bringing Palmer’s guard down, and a short right hook upstairs felling him again. Palmer swayed forward, whirled around and toppled over.

Two minutes and 33 seconds was all it took for McGovern to become the true world bantamweight champ. Legendary heavyweight John L. Sullivan stormed the ring and congratulated him. The crowd went crazy and the local sheriff had to calm a lot of rowdy spectators down. New York paper ‘The Sun’ said the 8,000 spectators were dumbfounded about the result. It was the first world title bout under Queensbury Rules to end in a first-round knockout.

"I knocked Palmer out several rounds earlier than I expected to," said the new champion, "but I felt sure I would do it sooner or later. I went in looking for a hard fight, and came out the winner, without a scratch, after fighting less than three minutes. Some are already speaking of an accidental blow. There was no accident about this."

The former title claimant was in damage control mode, as many fighters are when they are defeated. He also contradicted himself so blatantly that McGovern’s blows must have scrambled his senses:

"My being knocked out by McGovern was to some extent an accident. The fight was perfectly fair, and I lost. The blow was fair too, and it was a clean knockout, the first one that ever came to me. But two minutes and forty seconds of fighting does not give a correct idea of our respective abilities."

To the contrary, I would argue that it perfectly encapsulated McGovern’s abilities.

"McGovern’s great fight", read the headline in ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’, likening its local boy to "John L.Sullivan in miniature".

At this time Sullivan - the former heavyweight champion - was still seen by many to be the greatest pugilist that had ever lived. The same article labelled his fans ‘Gowanusians’ and said they were "firmly convinced he can beat Jeffries"; a tongue-in-cheek remark referring to James J. Jeffries, the current heavyweight champion and then seen as the best active fighter in the world.

McGovern’s pound-for-pound prowess cannot be understated: cartoons of the time showed bodies behind him and the greats of the era lined up in front of him, spooked, getting larger and larger down the line, including the likes of fellow pound-for-pound terror Bob Fitzsimmons. These were humorous depictions, but telling: McGovern’s ability to wreak havoc was not bound by weight.

The Chicago Daily Tribune, 4th February, 1900

McGovern was so confident of beating Palmer he had not only bet on himself, he had made arrangements to fight for the world featherweight title just a few months after.

But the now ‘world’ bantamweight champ would still manage to drub a few more quality fighters before he challenged for a second world championship.

McGovern fought all-comers, beating two opponents in one night in Ohio ("the hardest puncher ever seen in the local ring" according to one report) and in Chicago, including Patsy Haley again, this time inside of one round.

He also fought Billy Rotchford, the Chicago bantam who had been the distance with the great Jimmy Barry and lost via disqualification to Pedlar Palmer. After Palmer Rotchford had lost twice more, another ‘DQ’ and a points loss, both to a former foe of McGovern’s in Harry Forbes. However, he had also taken the ‘0’ of one William J. Rothwell, better known as Young Corbett II, a man who would become a legend in his own right a few years later.

What is mainly notable about Rotchford’s win over Corbett, is that he beat him over 20 rounds in the future champion’s Colorado back yard. Also notable is that he went the distance in the first place as Corbett was heavy handed. The bout was pitched to Corbett’s fans as being for the world bantamweight title, though of course this was far from the truth. But Corbett was already a local sensation, and in front of a packed arena Rotchford - who weighed under the modern bantam limit - easily outscored and countered Corbett’s wild swings. Corbett also had a decided advantage in weight, as he came in well over the stipulated 120lbs. Rotchford won the decision for "aggressiveness and superior science".

Billy Rotchford

Never stopped, and having fought some of the best men the lower weights could offer, Rotchford should have been a stiff test for McGovern, especially in Chicago, where Rotchford lived. Instead, Rotchford was left "groping helplessly on the mat" after being knocked down five times according to one local report, and McGovern’s local paper ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ said Rotchford was "helpless and groggy" in a one-sided fight. Another skilled opponent that could not even survive a round with McGovern.

Rotchford would only be stopped one more time in his career, coincidentally enough in the first round as well. The man to turn the trick would be one Harry Forbes.

Despite fighting eight times less than three months after his championship winning fight against Palmer (all knockouts, naturally) McGovern’s stiffest test would be his rematch with Forbes. It would also be a homecoming for McGovern, who had taken his knockout power on the road. He was now a big attraction wherever he went.

Forbes was confident of winning, and reports indicated he he would be a good test for McGovern. His speed and footwork had given McGovern some issues first time round, and he boasted draws with Tim Callahan and feared knockout artist Oscar Gardner, and wins over Eddie Sprague and the aforementioned Billy Rotchford. Against Gardner, a long rumoured suitor for a dust-up with McGovern, Forbes had survived a knockdown and scored two of his own to earn a draw. Gardner forced the fight, so Forbes must have held his own to be given a fair share of it.

"McGovern has already had a taste of Forbes’ quality, and realizes that he will have no such easy task as he had in Cincinnati on Monday, when he knocked out two men in three rounds”, said the ‘World’ pre-fight report.

The same report gave Forbes his due for being "an exceptionally clever fighter", and called him a "remarkable two-handed fighter", likely referring to Forbes’ quick left jab, as well as the sharp right hand which felled Gardner.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ acknowledged that both looked strong and in great shape at the weight, but that "Forbes looked like a weakling beside the miniature Hercules". McGovern’s neighborhood paper sure loved him.

In their first fight, Forbes’ quickness and ring smarts had stifled McGovern somewhat, but the Brooklyn boy had found the knockout punch in the end. For this fight, made at 118lbs (the modern bantam limit) McGovern was world champion, but Forbes started in much the same form as in their first duel.

The ‘New York World’ telling of the fight said Forbes "had the best of it" in the early going, winning the battle of "fiddling, feinting and leading", avoiding McGovern’s wild blows and timing his counters well.

McGovern just smiled, and even took time to acknowledge some friends in the audience. But when he tried to fire back, Forbes was smart enough to evade him. The Chicago challenger then landed a stiff left to McGovern’s mouth. "The little wonder looked puzzled" according to the same report.

The ‘Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ report credits McGovern with a knockdown in the first, although other reports do not mention this. On the contrary, the ‘World’ report noted that the only meaningful blows in the first were landed by Forbes.

Perhaps encouraged by his earlier success, Forbes was eager to mix it up more in the second round. He rushed McGovern and swung both fists at him. "Many of his blows landed, but in the mean time Terry was swinging also", said the ‘World’ report. Forbes had willingly jumped into a wood chipper. The ‘Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ report saw a right hand upstairs and a left to the gut, the ‘World’ merely a "left swing", but whatever the punch Forbes went down "dazed" and a nine-count was the result.

Forbes did not get on his bicycle or wrestle with McGovern to try and clear his head. Instead, "he seemed to lose his head and rushed wildly and pinned Terry to the ropes, where both indulged for half a minute in the most terrific infighting seen in a long time". The ‘New York World’ said Forbes was desperate. The crowd jumped up, cheering on the action. It was a war. In the mayhem it was not clear just how much damage Forbes was doing, "but it looked like McGovern was going to be whipped" as Forbes was "fighting him like a tiger".

Many top fighters had folded at their first brush with McGovern’s gloves. But Harry Forbes, buoyed by surviving the hard hitting Oscar Gardner perhaps, was not going to go down without a fight.

It would be his undoing. As Forbes windmilled away, McGovern timed him with a short right hand jolt to the jaw and Forbes dropped like a sack of potatoes. The referee started to count, but the blow was clearly a devastating one as Forbes’ seconds immediately rescued him. "He had no sooner struck the floor than his seconds threw up the sponge, but there was no need for this as there was no possibility of Forbes being able to regain his feet," said the ‘Daily Eagle’ report.

First time round, Forbes had battled his way through 14 rounds before being blasted. This time, with more experience on his side, he hadn’t got out of two sessions without being lumped.

McGovern had cleaned out the lower weights. Only Jimmy Barry had eluded him, and he was retired, now part of Harry Forbes’ management team. After that display, the undefeated little legend was never going to coaxed back into the ring.

Forbes was not disgraced, but McGovern was clearly the man at bantamweight, and perhaps beyond. There was one topic of conversation among those in attendance following McGovern’s second round knockout win: “What will he do with Dixon”?

George Dixon: World Featherweight Champion

It is not hyperbole to say that George Dixon was the greatest pound-for-pound fighter that had ever lived by the time the 20th Century rolled around. Only the great Bob Fitzsimmons could argue that, but Dixon was right there with him.

Since the inception of Marquess of Queensbury rules and gloves becoming commonplace, boxing had started to mould itself into the sport we know today.

Not that it was completely modernised. You could argue that it didn’t really get there until the ‘Walker Law’ came in, and that was 20 years after George Dixon put his dukes up against Terry McGovern.

But in these years, where fights to the finish could still be found, and 25 rounds were the domain of champions, George Dixon was the man.

Heavyweights were still seen as the gold standard, but Dixon was given due respect for his feats, even being black in a time where it was anything but easy to be so in America.

The first black world champion in fact. The Canadian had claims to both the bantamweight and featherweight titles in his career, and as the title was often used to promote a bout the division limit would lay at whichever weight was suitable for the contest at hand. Thus Dixon defended his featherweight title at the accepted limit of 122lbs, but also at 126lbs and even north of that.

Dixon is excluded from this list due to his bantamweight claim being at 114lbs (outside of the parameters set in the introduction) and as aforementioned for his great career being spread around in weight. Most pertinent to these rankings, he sometimes fought at 118lbs.

We’ll get there. But it must be said that George Dixon was not a man to be trifled with, even with at least 94 bouts on his ledger and almost certainly many more in a prizefighting career of over 14 years. The latter figure is a long enough career today, even with the advancements of sport science and sporadic fighting schedule the best of modern times keep.

But like anyone with that heavy schedule Dixon was not in his absolute prime when he fought the surging Brooklyn banger.

‘Little Chocolate’ was a man of science, of feints and jabs, of strategy, of the long mill. He was a boxer who could outclass his man and take them out once they had nothing left, but not a big puncher. He was precise and cunning, and he could hurt men, his supreme skill matched by his aggressive nature. In his great career he had bested the likes of Nunc Wallace, ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy, Cal McCarthy, and Eddie Santry. He could easily go tit-for-tat with larger fighters, such as the defensive savant Young Griffo, future lightweight champ Frank Erne, and was so durable he could hang in there with harder punchers such as Oscar Gardner.

Gardner is an important one as Dixon had beaten him over 25 rounds a little over a year prior to his fight with McGovern. At this time in the lower weight divisions Gardner was held in high esteem, and as a puncher there were few near to him.

Hard-hitting Oscar Gardner

He was not unintelligent either; he was crafty enough to get his shots off on Dixon, who was not over awed by simple slugging types. He gave Dixon a beating, and Dixon found him hard to hit in return, at least in the early going. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ opined that it was likely the hardest fight of Dixon’s life. ‘The New York World’ observed Gardner timing Dixon’s rushes with well-timed counter punches. Gardner ducked under Dixon’s blows and hit him with right hands to the midriff. One of these right hands landed just under the heart and "sounded like a blow from a hammer".

But by the end of 25 fast and scientific rounds, Dixon had won. The crowd hollered, but some reports found it a fair decision. Dixon had been aggressive throughout, and in the later rounds had jolted Gardner’s head around with his right hand, and been effective with his left hand too. It was "manifestly just, although it did not meet with the approval of the audience," said the ‘Daily Eagle’.

Dixon had met a younger, fresher fighter who was able to mix up his approach, had suffered a badly swollen eye, and braved the punches of a true knockout artist. It’s the kind of fight that can take years off a fighter, especially an ageing champion.

But Dixon kept on winning. He had lost and regained his title before, and was riding a 14-fight unbeaten streak when Terry McGovern came’a’callin’.

But context is important. We cannot just assume that Dixon was the great fighter of yore.

‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ had indeed given Dixon immense credit for his fight with Gardner, even with the decision being unpopular in some circles. Part of the territory for a black fighter in these times, of course, but reports found Dixon’s class undeniable. The ‘Daily Eagle’ report described the contest thus: "Dixon made a wonderful fight and showed all his old time speed and cleverness."

So the featherweight champion was still a force to be reckoned with. But another 12 months and ten fights can add mileage onto a veteran fighter, especially as Dixon was fighting top-class fighters regularly.

We met Tim Callahan earlier: he was the shifty and durable Philly pug who McGovern served his apprenticeship against. He continued to be a notable fighter for years. He faced off with Dixon in October of 1899.

"Dixon would have received the decision had any been given," said a ‘Philadelphia Inquirer’ report. Dixon’s left hand had dictated the fight, although another report said that Callahan showed his standing near the top of the division was legitimate.

This report was in the ‘Philadelphia Times’, and the observation was made that "Little Chocolate has lost much of the speed that characterized his more important fistic encounters".

Still, the same report also said of Dixon that "there is no more noted and clever fighter in the world today", so he was still highly respected.

Subsequent fight reports follow the same pattern. Dixon was winning, often clearly, but there was a clear downturn in the quality of his performances.

Will Curley was a young Tynesider who was slated to fight Pedlar Palmer. Some British reports felt Palmer had swerved him by venturing Stateside to fight McGovern, a decision that had ultimately been disastrous.

Will Curley

Curley had an educated left hand and put it to good use in diffusing the wild rushes of ‘Torpedo’ Billy Murphy. He deferred from using his right hand for much of the fight, so when he eventually threw the backhand it caught Murphy by surprise. ‘The Sportsman’ saw Murphy "dropped to the boards as if shot". His seconds saved him right away.

Curley also had a 20-round decision victory over Patsy Haley. The Englishman was a good fighter who likely had more bouts than his Boxrec page shows, and came highly touted when he challenged Dixon.

"Curley had evidently been well schooled as to Dixon’s manner of fighting and his teaching showed itself in his clever blocking," according to ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’. But Dixon’s aggressiveness won him the fight, stunning Curley in the fifth, and dropping him with a left hook in the eleventh.

Dixon could not finish his man, and had to settle for a decision after 20. The same report said that "judging from his showing it is doubtful if he will be able to hold the title much longer". Dixon was not as precise as he had been in his prime, though he was still effective.

Dixon’s final fight before he took on the world bantamweight champ was against Eddie Lenny, a useful fighter who was marketed as undefeated but was anything but. But he was a solid contender, and ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ noted he was "remarkably clever". Recent results included draws with Harry Forbes, Joe Bernstein and Patsy Haley, so he was clearly capable of mixing it with world-class opposition.

The reports afterwards read much as they did after Dixon beat Curley.

"Although he won by a large margin, Dixon showed plainly that that he has lost many of the qualities that have made him the foremost bantamweight fighter in the world. He is not nearly so fast as he was and his blows lack the force that once made him a terror," said the ‘Daily Eagle’ report.

Dixon, of course, was the featherweight champ, but could still make the lighter weight and had previously held claim to the world bantamweight champion.

The current world bantam champ was the scariest man in boxing. Dixon would have to be in better form than he had been in recent times.

The Champions Prepare

Dixon was on the downside of his career according to contemporary sources. He had told anyone that would listen that his fight with McGovern would be the last of his career, and that he had trained even harder to ensure his final bout went in his favour.

It’s easy to look at an aging champ and assume he is an easy mark, but even with McGovern favoured to win, Dixon was given his dues.

A pre-fight report printed in the ‘New York World’ claimed McGovern was training for "a bruising fight", seeing Dixon as "a better man than he has ever faced before".

The ‘World’ felt so too, commissioning a portrait of Dixon before the fight. The headline for it read: ‘GEORGE DIXON, THE GREATEST OF ALL FIGHTERS’. The training report that ran with the portrait saw the upcoming contest as "the greatest contest between little men ever seen". The world bantam champ versus the world featherweight champ: today we call these super fights.

Dixon’s manager Tom O’Rourke said Dixon was in fine fettle, and had been looking forward to this contest for months, moreso than any other. Three days before the fight he was at 117lbs.

‘The World’ commented on the odds: McGovern was a 2-to-1 favourite, and they claimed these ridiculous odds even given his impressive run of knockout victories. Dixon was too excellent to count out, even given the wear and tear and his prime tapering off.

On the day of the bout, they wrote:

"There seems to be a perfect mania among ring followers to bet on Terry McGovern at 100 to 60, or even at 2 to 1 if they can’t get better odds. What the mania is based on is rather hard to tell. Terry is a wonderful boy, no doubt, but so is the little bronze champion. Careful observers of ring events are unable to figure out a line on public form to justify the giving of such tremendous odds of 2 to 1.

"With Dixon in such excellent condition, it is interesting to look over his record and inquire what he has done to justify people betting against him. He has been feather-weight champion for ten years. He won the title from Cal McCarthy, one of the hardest hitters ever seen in the ring at feather weight, and who fought in a style very much like Terry McGovern’s. Besides successfully defending his title against all men of his size for ten years, Dixon has fought draws with such big fellows as Frank Erne, the present light-weight champion, to whom he gave away fourteen (pounds) in the ring. He beat Martin Flaherty, a first-rate lightweight. Indeed it is safe to say that Dixon has given away five to twelve pounds in practically all his fights."

The article went on to point to Joe Bernstein surviving McGovern as reason to believe Dixon could do the same. Of McGovern’s best opponents (Harry Forbes and Pedlar Palmer) Dixon had more experience than both of them combined.

But styles make fights as much as ring experience. Tommy Ryan - world welterweight and middleweight champion - was a legend in his own time, and so scientific he also trained fighters.

Resorting to a cliche, he had likely forgotten more about boxing than most observers would ever know. He weighed in on the bout:

"Dixon and McGovern should put up a great battle when they meet. I don’t care to tip a winner in that bout, but I will say this: Where one man punches straight and the other swings all the time, the straight puncher instantly gets the money. Dixon depends mostly on swings, and Terry hits straight as a die. So you can decide for yourself who ought to win."

McGovern, of course, was as much of a swinger as Dixon, but he could throw straight lefts to the mush and some accounts of his right hand read like crosses. Perhaps this is what Ryan was referring to.

McGovern’s pound-for-pound qualities were also noted. He sparred a wide range of different opponents, presumably to prepare him for the various qualities Dixon possessed. In one day he sparred with men weighing 160lbs, 133lbs, 122lbs, and 110lbs. He skipped and went for a light jog, and was a mere pound away from the contracted 118lbs weight limit. McGovern was sparring and training with Danny Dougherty (who was likely the 110lber referenced above) an excellent bantam in his own right. The bantamweight champ was said to be "in fine trim". The ‘World’ saw McGovern claim to be "taking a rest," but saw his "resting" regime as something "the average person would call the hardest kind of work".

The ‘World’ had emphasised that Dixon was the most experienced and talented opponent McGovern had yet met, but the ‘Syracuse Post Herald’ also felt the opposite was true. They saw McGovern as "Dixon’s greatest adversary", "a terrific hitter and fast two-handed fighter" who was "absolutely fearless". They saw in McGovern’s backers the feeling that it was ‘a physical impossibility for Dixon to withstand the "terrific rushes and heavy blows" that McGovern would attack him with.

The same article also referenced the aforementioned Dixon vs Gardner clash. Gardner had "failed to distress Dixon at any stage", which was true, and Dixon supporters were arguing that McGovern was not Gardner’s superior in punching power. This was a fair argument to make. Dixon’s speed may well have been running away from him faster than an outmatched opponent, but he was very durable, and had never been knocked out in a legitimate contest.

Kentucky Rosebud, artists impression

Dixon had been knocked silly once though, in an exhibition six years earlier. The opponent that time had been ‘Kentucky Rosebud’, a tough fighter who fought many of the best fighters around. It was just a simple go around for the pleasure of spectators, and Dixon had treated it as such. Seeing Rosebud was out of his depth, he started to clown him, and was met with a sock on the jaw for his troubles. Dixon was completely unconscious and it took a few minutes to revive him. Once stirred, he continued with the exhibition - just light work - and finished the agreed-upon three rounds.

To use a well-worn boxing adage, ‘sparring is sparring’, and this is all we can draw from this. When on-song in a genuine fight environment, Dixon had never been knocked out. He had rarely been knocked down. He fought the Kentucky Rosebud on legitimate terms many times after the exhibition and had never lost to him.

He wouldn’t make the same mistakes against McGovern. Dixon was known to be easily distracted outside the ring, and was a heavy drinker. For this fight, he had been more focused than he had been in years.

The ‘Syracuse Post Herald’ saw it thus: "If Dixon is to be knocked out it will be proof that McGovern is the wonder of the pugilistic avenue."

The Day of the Fight

The Dixon-McGovern fight was a huge attraction, ‘The New York Times’ stating that sporting fans had traveled from all over the country to see the fight.

A fight day report in the ‘Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ described the fervor as such: "To say that the attention of the sporting world is concentrated upon the Dixon-McGovern meeting to-night is putting it mildly, for on all sides the battle is regarded as the greatest between little men that ever took place."

Dixon’s condition was astounding, just as Tom O’Rourke said it would be.

“I haven’t seen George show so much snap and life in his work for years”, said his longtime manager. He was betting $5,000 on his man to win.

The ‘World’ said Dixon’s physique "will surprise the wise men who have been betting their money on the theory he has gone back".

“I’ll fool some of these 2-to-1 fellas tomorrow night," Dixon laughed. He was supremely confident.

McGovern had to sprint out the last few pounds on the day of the fight. He had never looked better according to the ‘World’.

A letter from McGovern was printed in the same publication:

"I expect to beat George Dixon tomorrow night, but I’m not looking for a picnic. I know he is the greatest little man we ever had in this country, but that will give me all the more credit for defeating him. When I beat Palmer, the English champion, it was so easy that lots of people thought it was no fight at all. The fight with Dixon won’t be like that. It will be a great battle, but if I didn’t expect to win I wouldn’t get into the ring. Dixon is bigger than I am, but I know he isn’t any stronger. He is taller, but I weigh as much as he does, and I’m ten years younger. He’s a champion, but a champion will fall down as hard as any other man if he’s hit in the right place."

They both made the stipulated weight at 3 o’clock. Six and a half hours later, they would be in the ring together.

Dixon was said to be "a little drawn" as he had been training so hard. McGovern smiled and chatted with his seconds. It was announced to all that the bout was to be contested under Queensbury Rules, so hitting in the clinches was permitted. McGovern squared up to Dixon in the centre of the ring as the rules were explained to them both. Neither of them needed any reminding. They were both in prime condition and there was nothing left to do but fight. The greatest little man there ever was against the scariest little man of the day. Champion versus champion.

The following round-round-account of this classic match draws from next day reports published in the following publications: 'The New York Times'; 'The Brooklyn Daily Eagle', 'The World,' 'The Evening Herald: Syracuse', 'The Boston Globe', 'The Boston Post'.

Round One

Dixon led with his left but it sailed over McGovern’s shoulder. They clinched and both fought furiously with their free hands. McGovern landed a series of right hands, either "over the kidneys" or "six right-hand smashes on the short ribs". Dixon jabbed McGovern in the mouth. Dixon landed a left hook to the body and the same shot upstairs, but it had no visible effect on McGovern. Dixon was then "shook up" by McGovern’s body shots, but he landed a counter left to the jaw that shook the Brooklyn boy up. "George showed he was the Dixon of old" with his showing. The bell rang as they were trading blows.

Round Two

Dixon landed an uppercut to the belly, but McGovern just laughed at him. McGovern smacked Dixon around the kidneys. A left to the cheek from Dixon had McGovern laughing again. Could McGovern have been trying too hard to show he wasn’t affected by Dixon’s punches? One left hand from Dixon had McGovern halfway through the ropes, but he recuperated quickly and set about the body. A jab from Dixon drew blood from McGovern’s mouth, but Dixon had to hang on in the clinches when McGovern battered him to the body. McGovern let a left swing go around his neck, showing his defensive reflexes off. McGovern’s superiority on the inside and Dixon’s cleaner blows saw reports divided on whose round it was.

Round Three

McGovern was exclusively utilising short whacks to the body at this stage. Dixon shot a wide left out, but "Terry protected himself beautifully". Dixon tried a jab but McGovern countered with his own left to the cheek. Dixon rushed again but McGovern ducked and "smashed him in the belly three times with hot rights". According to his hometown paper the ‘Boston Daily Globe’, the featherweight champion displayed the "fiercest speed" he had in years. Clearly he was being truthful about how hard he had prepared for this fight. "Three hard swings with right and left on the jaw somewhat embarrassed McGovern in the third round, and it looked for a moment as if he might be knocked out," according to ‘The New York Times’. The ‘Daily Eagle’ saw it as a right hand, which shook up McGovern "so severely" it had won the round for the featherweight champ. McGovern had kept a cool head to withstand Dixon’s pressure.

Round Four

Going into the fourth round, gamblers could get even money on Dixon, such was the nature of his showing. McGovern got in close, perhaps to stay inside the range of Dixon’s hooks. He shifted to his right and landed a right hook high on Dixon’s cheek which staggered him. Dixon sank almost to his knees, but showed gameness to stay up. Dixon returned to his corner puffing and panting.

Round Five

Reports say that the featherweight champ seemed weakened by the big right he had copped in the fourth, but he was staying cool. Dixon was using his left to perfection, and McGovern had to show "the grit of a bulldog" not to capitulate. McGovern roughed it in the clinches, using an open glove in Dixon’s face to control his form. The crowd hissed at McGovern. An even round by most accounts.

Round Six

Dixon chopped McGovern with two lefts around the right eye, then changed the trajectory of his shot on the third left, catching McGovern to the ribs. McGovern winced, as he had been caught in one of Dixon’s traps. "Terry appeared to gain in strength," according to the ‘Brooklyn Daily Eagle’. A left to the jaw had Dixon reeling. Dixon recovered straight away. McGovern’s body attack began to tell on Dixon, and he looked tired and bruised. The older man was still given a good chance to win the fight as the round came to a close.

Round Seven

Dixon shot a left to the body but it was blocked. A left to the head was evaded by McGovern’s "clever ducking". Dixon looked very tired in this round. The ‘Daily Eagle’ saw this round as the one that turned the tide. They reported Dixon’s nose was broken and that he was clinching constantly, just to try and quell the constant body blows.

Round Eight

‘The Boston Daily Globe’ reported that Dixon’s training schedule was paying dividends as he regained his sprightly legs at the beginning of the round. McGovern was dipping as Dixon jabbed, letting the blows fly harmlessly over his shoulder. Dixon went for the head but McGovern blocked the punch and sent a right jolt into Dixon’s jaw, dropping him in a heap in his own corner. ‘The Brooklyn Daily Eagle’ saw this as more a slip. More than one report credits McGovern with helping Dixon up, so this was likely a slip. Dixon rushed McGovern, but the younger man planted his feet and threw a right hand haymaker to the ribs, which crumpled Dixon to the mat. ‘The World’ said that McGovern helped Dixon up again! More body shots had Dixon down on all fours. He got up at five. Dixon was praised in reports for his tenacity here, but McGovern was all over him. Dixon went down with a right to the jaw, and lay flat on his stomach. As he tried to rise again, his manger O’Rourke threw in the sponge. Dixon had been down five times, and could not hold off McGovern any longer. It was the first legitimate stoppage defeat of his long and illustrious career, and ‘Terrible’ Terry McGovern was a two-weight world champion.

After the fight

McGovern was a star beforehand but after defeating Dixon he was a hero, lauded as the very best fighter in the sport. In the aftermath, he gave credit to the now fallen champion:

"I have at last beaten the greatest fighter of them all, and the featherweight championship is mine. I have worked hard for it during the last two years. I have beaten some good men in that time and taken some heavy punches, but the hardest fighter and as game a man as I ever met in the ring is George Dixon."

Dixon was apparently inconsolable after the fight. He had wanted to retire as champion. His good friend Joe Walcott, ‘The Barbados Demon’ who - like McGovern - was one of the hardest punchers of the era, had to be restrained by policemen after rushing the ring. He was distraught at the violent beating his friend had received.

Contrary to the actions of his good friend Walcott, Dixon was as classy in defeat as he was in the ring:

"I was outfought by McGovern from the end of the third round. The blows on my stomach and over my kidneys were harder than any I ever received. I have been fighting for fourteen years and I have met men in the light-weight class ten pounds heavier than McGovern was to-night, but not one of them could land a blow as hard as those that he sent in. He is a wonderful fighter and fairly won the championship. He has my best wishes."

Reports of Dixon’s fights preceding McGovern had observed a great champion slipping from his best form. Accounts of his fight with McGovern noted that with the class he showed ‘Little Chocolate’ would have beaten most if not all of the other contenders around. He was not at his peak, but he had worked himself into incredible shape and was driven, moreso it seemed than he had been to fight Will Curley and Eddie Lenny. Terry McGovern was just too good for even the great George Dixon to overcome.

The ‘Boston Daily Globe’ summarised the fight thus:

"Battle will live in history as one of remarkable courage on the part of a ring veteran who found his match in the youth and vigor of an opponent in the very last bout of an extraordinary career of success."

Sadly, despite his herculean effort and the respect he gained even in defeat, this wasn’t Dixon’s last stand. He lived as hard as he fought, and gambled and drank his prizefighting money away as quickly as he could punch it into his pocket. He mixed in the best company available for the rest of his career but lost more than he won, and died a pauper at the age of 37 a few days shy of the eighth anniversary of his bout with McGovern.

Terry McGovern had ripped the last of Dixon’s prime from him with his horrific body blows. But for the hard-punching Brooklyn dynamo, his prime had just begun.

‘Terrible’ Terry

To discuss the rest of McGovern’s career I would need a few hundred more pages, for even as a two-weight world champion with a win over one of the all-time greats of boxing what followed is even more extraordinary.

The long-awaited battle between McGovern and Oscar Gardner was as savage and violent as you would imagine. McGovern was badly hurt and nearly knocked out in the first round, but rallied to knock Gardner out in the third, a left hook "laid him out like a pancake".

McGovern knocked out Eddie Santry to end any claim of there being another featherweight champion. Santry was supposed to be a stiff test for McGovern, but he was outclassed and stopped in five.

He knocked out the tough Eddie Lenny inside of two rounds, beat Dixon over six in a rematch, knocked out the world lightweight champion Frank Erne in three rounds (in a non-title fight), saw off Joe Bernstein in seven (no chance of surviving for Bernstein this time) and capped off the year with a sensational two-round demolition of Joe Gans.

The win over Gans is disputed to this day. Gans later said he threw the fight, and those in attendance didn’t think they saw a scrap that was on the level. Given McGovern’s standing at this time, the fact it still isn’t a cut and dry case of a fixed fight is testament to the savagery he dished out over any weight he could convince someone to fight him at.

Perhaps the most startling thing about these exploits? They were in a single calendar year. The first year of the 20th Century was ushered in by McGovern seeing off the greatest fighter of the previous era. By the end of the year he had staked his claim to being the greatest of all time.

Like Mike Tyson after him, McGovern’s reign of terror was short lived. After a brief and brutal bout with the undefeated knockout artist Aurelio Herrera, McGovern was shocked by Young Corbett II, the same man we met earlier as a Coloradan prospect losing to Billy Rotchford over 20 rounds. He mocked McGovern, drew him into a war and knocked him out inside of two rounds.

McGovern was never the same again. Although he fought at a high level for the rest of his life, he was never able to regain a world championship. He put forth a stronger performance in a rematch with Corbett, but was stopped in 11 rounds. In the rubber match, McGovern got off the deck to claim what most newspapers agreed was a draw.

He retired in 1908, aged 27, a young man but a veteran of nearly 80 fights (that we know of!).

For McGovern, life after the ring appeared to be fruitful. The same man who as a boy donned the gloves in order to provide for his family had one of his own, and found success as a businessman.

"Terry McGovern, the former featherweight champion, has branched out as a full-fledged real estate agent, with an office at 215 Montague Street, Brooklyn. Terry says thus far he had cut out a rapid pace, as strong as when he was in the zenith of his glory in the roped arena." - The New York Times, 12 April 1909

But things quickly turned sour for Terry. He had lost a child in 1904 (some reports say a girl, some a boy) and this, coupled with the devastating loss to Young Corbett II, caused him to become depressed. The clean-living McGovern also turned to the bottle.

Did McGovern’s many wars in the prized ring also contribute to his mental state? Pugilistic dementia was not even known of in these days, although of course too many hard fights were known to send a man to dark places.

McGovern’s friend, the great John L. Sullivan didn’t think so:

"The report that Terry McGovern has gone to pieces has raised the yell, 'There’s the result of prizefighting'. But it isn’t. Terry didn’t break down because of fighting, but because of the death off a child and disappointment. The actual fighting didn’t undermine his health."

But by 1909 McGovern seemed to have found steadier ground with the opening of his realty business. Yet three months after the reports of his new success, McGovern had fallen to pieces again.

‘The Middletown Daily Argus’ published a report of McGovern’s woes in July 1909:

"A shadow of his old self, Terry McGovern, once featherweight champion pugilist of the world, was taken to a sanitarium at Amityville, N.Y.

“I want to go home, I want to go home”, pleaded Terry when friends tried to get him into the automobile that was to take him away. After much persuasion he agreed to go if his mother would ride in the car with him.

"McGovern had been in the observation ward of the Kings County hospital. He is a nervous wreck, but his friends hope that the treatment he will undergo will set him on his feet again, as it did after his breakdown several years ago soon after he lost the championship."

McGovern, the once fearless and indestructible two-weight world champ, was all but lost. Judging by the reports, he had been suffering with mental health problems for years, and decades later he wandered into a hospital, penniless and in need of care.

He died aged 37, just as his great rival George Dixon had. A tragic end for ‘Terrible’ Terry McGovern.

McGovern: The Great Bantamweight

McGovern was - for my money at least - one of the ten greatest pound-for-pound fighters that has ever lived. The year in which he tore through three weight classes without resistance is quite likely the most astonishing calendar year any boxer has ever had. At bantamweight (yes, bantamweight) McGovern was simply unbeatable. By the rules set in the introduction of this series, he has the distinctive honour or winning two world championships inside the weight allowed: his world bantamweight crown against Pedlar Palmer, and the featherweight title from George Dixon.

So why number two?

Quite simply put: it’s a hunch. A hunch on my part that boxing technique developed in the following years, a hunch that boxing stretching its ropes around the whole world brought about a far healthier and combative environment for the world’s best fighters, and in particular those at the lower weights. Before long the world would see that there were excellent fighters in the Philippines, Mexico, and later Japan and Thailand that had just been waiting to be given a pair of boxing gloves, and that filled out the ranks of the lighter weights considerably.

McGovern beat the best of Canada, the U.S and Europe. The contemporary opinion of these fighters is that they were uniformly great. The perception of them all today among historians is that they were all supremely talented for their day, and in George Dixon the man they called ‘Terrible’ Terry has possibly the best single win in the history of the division.

However, the scant footage of Dixon (in an exhibition closer to his death than his fighting prime) shows us a wild fighter far removed from our perceptions of what a world-class boxer should look like. Even with old man Dixon most likely mugging for the camera, it doesn’t inspire confidence in the modern eye that Dixon was all that a fighter in reality, only for his day.

The sole surviving footage of McGovern is unfortunately of the fight with Joe Gans, which historians lean toward labelling a fix. No evidence has ever been offered supporting McGovern’s involvement in fixing the fight, and the opinion is that he was not aware that Gans was taking a dive. So perhaps we can take his own performance at face value.

What the footage shows is a raw and aggressive fighter. A modern comparison would be to Marcos Maidana before he began training with Robert Garcia. McGovern looks unhinged but not without ring smarts, swinging wide punches to force Gans to move where he wants him. McGovern also shows a sneaky inside uppercut, which looks no different than the punch Roberto Duran would use to great effect some 70 years later. When he gets into a wide stance he is reminiscent of Fighting Harada at his swarming best.

Gans’ lack of resistance means we don’t really get to gauge just how McGovern really fought. Watching a top level fighter beating a man unwilling to fight back never teaches us anything, but for the curious it is still a fascinating piece of footage.

But would McGovern, the second greatest bantam of all time on this list, be able to compete with the great fighters who came after him? We will never know, although he was certainly a tremendous puncher, an attribute which stands the test of time. He is ranked here for his prowess in his own era - a highly competitive one - and the wide array of excellent fighters he beat within the weight limit allowed.

It is McGovern, not Jofre, not Harada, not Pete Herman, that is the greatest fighter to ever fight in the bantamweight division.

But not the greatest bantamweight of all time.

Imagine a fighter with McGovern’s soul-consuming power and aggression in the bantamweight division after boxing had been through international expansion, a fighter who spent all of his prime years among the world’s best 118lbers.

Luckily for us, there is no need to imagine this surely mythical fighting force. The greatest bantamweight of all time was just that.

Kyle McLachlan would like to express his thanks to Sergei Yurchenko for providing research material for this essay. He would also like to thank Boxing Monthly contributor ‘Joe Grim’ aka Gary Lucken for his assistance.

This article was originally published on boxingmonthly.com and was edited by Luke G.Williams. You can purchase Luke’s excellent book Richmond Unchained here