Emile Griffith: The Pragmatic Stranger

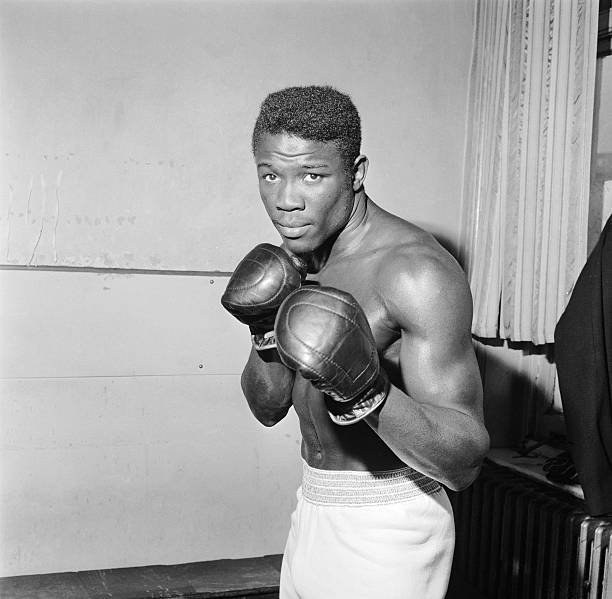

Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Introduction

Among the pantheons of geniuses and pugilistic greats, you’ll be hard-pressed to find as many divisions in boxing’s storied history with as many bonafide monsters as the welterweight division. Diagnosing any great fighter there isn’t exactly challenging, though once you start to separate the immortals from the rest of the pack, there are definite concessions to be made about what is really needed to be considered a king at the top of an already-impressive weight class. I’ve already covered the man who may well have been unstoppable at his peak, the eponymous ‘Sugar’ Ray Robinson, whose reputation speaks for itself, though I think it’d be unfair if we ignored the many greats who may well have contended for his throne if all were one era. Names such as Jose Napoles, an aesthetic and technical marvel, or another ‘Sugar’, Ray Leonard - a media darling whose interview demeanor betrayed the savage fury he unleashed in the ring — stand out. There are many others, including the likes of Kid Gavilan, Luis Manuel Rodriguez, Thomas Hearns, Floyd Mayweather Jr., and so on — boxing royalty all. Yet, I found myself drawn to one in particular: one Emile Alphonse Griffith — because, despite being qualified as great, it seemed intriguing that he wasn’t a fan favorite among his peers.

Griffith was introduced to boxing at some point in his late teens — seemingly almost by coincidence — while working at a factory owned by a relative of a boxing manager. Said manager introduced Griffith to the experienced and savvy trainer Gil Clancy, and Griffith’s amateur career took off. By 1958, the then-twenty-year-old Griffith was now a professional boxer. Nearly three years later, he was the best welterweight in the world. Griffith would have his losses, mostly incredibly competitive battles with some of the finer fighters of his generation. Outside of Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter’s first-round demolition of Emil and Jose Napoles’ shutout performance, Griffith never was out of those fights and very well could have won most of them. Griffith then turned his attention to middleweight and gave some of the finest fighters there all they could handle, even becoming a champion there. At the end of a nineteen-year career, Griffith had won 85 of his 112 bouts, had been a five-time world champion, and, most notable of all, had competed in 339 rounds in 22 title bouts — a record that holds to this very day. If there were three conclusions you could draw about Griffith, they were:

1) His success at two deep weight classes meant that Griffith was an immensely talented fighter.

2) Over the course of his career, Griffith’s ring generalship was melded by him becoming one of the most experienced boxers on the planet, especially in fifteen-rounders.

3) Though arguably the most defining feature of Griffith’s entire career was that he was met with enormous adversity and pushed forward regardless.

And yet, in my research, I found that none of those seemed to apply to how Griffith is remembered among those who aren’t boxing history aficionados. And, even for those who do know their history, Griffith isn’t remembered as the quintessential crowd-pleaser many fellow boxing legends are. Of course, I think we might be able to infer why:

First and foremost, Emile Griffith’s most famous career moment is a source of enormous discomfort and tragedy in boxing history. Regardless of the circumstances or the politics involved in-or-out of the ring, Griffith met one of his key rivals, Benny ‘Kid’ Paret, in a rubber match for all the marbles littered with hostility. The result was a fight so vicious that Paret would be confirmed dead in the hospital days later.

I don’t really think there’s an overview that truly encapsulates this topic and all of its nuances. If you want to know what I personally felt and how I think that night should be remembered, then you can read this thoughtpiece. Nonetheless, it is the event that is tied to Emile Griffith’s name. It almost made him quit boxing, yet he pushed on because, by all accounts, he didn’t have anywhere else to go than the boxing ring.

The second reason behind Griffith’s lesser acclaim is comparatively, less difficult to address, though it will serve as the crux behind the rest of this piece: how Griffith fought wasn’t exactly the most crowd-friendly and, most probably, is an acquired taste.

However, Griffith fought many of the finest pugilists of his generation and, even in losses, he proved that you needed to be an extraordinary one to even beat him for a reason. Ergo, how does one of the most consistent fighters you can find engage his opponents?

Simple Principles

In actuality, what may surprise you is that Griffith’s strategies are incredibly general: Griffith wants to ‘control’ his opponent, step in and force tie-ups, and deny them as much room to work as possible.

At range, Griffith would apply rangefinders, throwaways, feints and his counterpunching to control distance. He doesn’t use many tools; rather, it’s his application of those tools that counts. Admittedly, Griffith’s skillset was extenuated by his incredible physicality. The threat of tying up or exchanging with someone with Griffith’s gifts made his threats all the more effective.

That isn’t to say the actual tools individually would be ineffective alone however. Over the course of his career, Griffith developed a particularly skilled jab. While most jabs find their utility in how much they can do, Griffith made sure his jab’s utility was maximized within meticulously chosen purposes. Primarily, Griffith’s jab was for distance measurement and rhythm manipulation. At distance, it was used to draw and gauge responses from the opponent or used to turn them into a disadvantageous position or to give Griffith more space to work. I would go as far to say that the jab facilitated a good deal of Griffith’s ringcraft.

Where said ringcraft shined was his ability to get inside on his opponents or feinting an intention to tie-up with them through a variety of entries.

What you can see is that many of Griffith’s entries are crafted through a plethora of feints and using his opponents’ expectations against them. The level changes and jabs mess with rhythm and can draw responses out — where he’ll level change and then blitz in or dip below to tie up. Sometimes, he’ll even fake going for an entry to the clinch just to set up a power shot.

These are just some of the many ways Griffith found ways to force proximity. More prevalently, Griffith’s ability to mix his tools up or even use multiple tactics in combination made those entries incredibly difficult to predict and avoid, especially if the risk was being caught out of position by a committed punch. Many of Griffith’s actions were conceptually simple, but his constant input with each and every tool maximized their effectiveness and caused his opponents to overreact. After all, tying up with Griffith was where the fight got extremely harrowing:

On the inside, Griffith was an exceptionally calculating, savvy operator — among the best in the history of the welterweight division. Commonly, you’ll see infighters adjust their arms, shoulders and head position according to their opponent’s. Since Griffith was forcing so many tie-ups, it was imperative that he attempted to control every single one, especially versus competent infighters.

In particular, Griffith would look to position his head below or adjacent to the other man’s head. On the inside, placing your head under your opponent’s while burrowing your shoulder into their chest can force them to stand more upright and break their posture. Moreover, it makes it difficult for them to hit you because your head is buried into their chest and your shoulders and arms are often positioned inside of their reach. When they try to punch around, their punches will be caught or lose their steam. As a result, the opposing fighter has to reset their feet or attempt to fight grips (e.g. looking for underhooks or overhooks) or be forced to wait until the referee breaks them if they concede the tie-up to be a 50-50 exchange. In that sense, Griffith nullified his opponents and, once they separate, he can get back to work while they struggle to build. And when he got them to the ropes? They had far less space to reset or get out of the corner without tying up again and taking punishment to the ribs in the process.

Besides his head positioning, you’ll also notice Griffith looks to fight and control wrists or the opponent’s arms with underhooks or overhooks himself. Many times, clinches don’t just lend themselves to a chance to make the other man work — they can actually smother them and force the rhythm of a fight to temporarily stop and then reset. Part of what made Griffith so frustrating to fight was because if he would notice an opponent had some success, then he would find ways to enter the clinch and use that clinch to enforce his physical and inside fighting advantages at best or halt his opponent’s momentum at worst.

Watch how Griffith is always readjusting where his arms, legs and upper body are compared to his opponent to set up body shots or to smother their work or to give him just enough room to dig to the body or break the clinch on his terms.

Still, as terrifying a force Griffith could be when he had the other fighter cornered, he had one other trick that made him even more dangerous: where he would take advantage of the clinches or grips, break them off or turn the fighter into intercepting hooks. In other words, Griffith played with transitions on the inside just as well as he did on the outside to become a threat at any and all ranges. As the bout progresses, not only does Griffith’s well-conditioned endurance start to wear the opponent down, he would constantly make them unsure if he was looking to force them to the ropes, attack on the inside, or attack from the outside. These expectations, along with Griffith’s insane physicality and explosive power, made him a grueling opponent to overcome.

I’d go as far to argue that Griffith’s greatest strengths were his accuracy and opportunism. Griffith’s strategies, essentially, were fairly minimalistic, though he would scout and adjust versus his competition during fights continuously and constantly, regardless of how much they threw at him or against him.

Against superior jabbers, he would circle around them while still jabbing himself (often using throwaways) and then set them up with a counter if he couldn’t step inside. In particular, Griffith liked to employ a dipping L-step and followed by counter left hooks to catch his man unaware.

Against competent inside fighters, if he couldn’t establish full control on the inside, he set them up on the outside for longer exchanges by using his jab to draw counters and then used his left hook to close the door on exchanges. If he was on the inside, he looked to turn his opponent and separate.

And when Griffith truly was at his peak of offensive potency, he was an absolute terror. Gaspar Ortega was one of the greatest and most durable of all televised action fighters — capable of giving even the most elite fighters a good scrap. Griffith didn’t give Ortega a moment for free, tore him up in every phase and did what no one else could do — hand him one of his only two stoppage losses (the other one coming when Gaspar was past his best) to Ortega near his peak without even losing a round. It was a showcase for Griffith’s transitional and creative offensive powers.

Simply put, Griffith wasn’t simply an all-rounder, he was the definition of a fighter who knew exactly what he was doing minute-to-minute, which ensured a deliberate nullification or subsequent destruction of his opponent’s game.

The Double-Edged Sword

That said, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that Griffith’s game came with quite a few asterisks. For one thing, as much as Griffith did control a fight, his strategy — unless he really could take over a fight — led to many hard-fought, contentious decisions with significant amounts of stalemated tie-ups, especially if his opponent was extremely competent in all phases too. It’s a testament to Griffith’s in-ring experience that he won a great majority of these fifteen-round bouts, though it has to be said that a number easily could have gone the other way, especially if the other man threw his punches in numbers, such as one of his archrivals, Luis Manuel Rodriguez, whom Griffith controversially won an incredibly close series over.

Moreover, Griffith’s style forced him to be incredibly reactive and adapt around what his opponents could do. Subsequently, if another fighter keyed in on Griffith’s tendency to be caught on the lead or counter on his entries and exits, they could punish him for it, especially to the body. Despite Griffith’s ability to smother or negate successes, he couldn’t stop everything in excessive numbers — optically, that does count for something if fights go the distance.

Griffith’s defensive ringcraft when he wasn’t working in neutral space or resetting behind his jab also saw him with his back against the ropes on many occasions. More often than not, Griffith often fought his way out by trying to punch a hole through his adversary’s chest rather than trying to avoid that situation entirely again. Usually it worked, but there were definitely occasions when it simply wasn’t enough.

The only time, even if it was past his best, where Griffith was truly outskilled from bell-to-bell, for my money, was by one of the greatest technical boxers to ever grace the ring: Jose Napoles. He drew Griffith in, punished his entries with counters, and when Griffith was ready to fire back, Napoles was already one step ahead, exiting at an angle ready to punish Emile some more. Mind you, not many fighters are as brilliant as the Cuban great.

Speaking of Griffith’s physical capabilities, one of the most important lessons with any statistic is understanding that context matters. At this point, you may have noticed I mentioned Griffith being a thunderous puncher. You might be thinking the same thing I did: How is it that someone who can punch so hard have most of his fights go the distance?

Part of it can be easily attributed to how Griffith fought: not to the level of his opponent, but only to the necessity of the task. Griffith, I’d personally argue, was not a finisher who looked for the finish. If he did hurt his opponents, Griffith certainly tried — but his style was tied more to his strengths as a ring general.

There’s also, admittedly, some armchair psychology we have to possibly defer to here. I don’t normally take the words of accounts — fighter or trainer — for absolute granted, though I have to believe, based upon the many fights of Griffith’s career, that he was fairly hot-cold when it came to going all out versus his opponents — especially since he did have the propensity to hurt them bad when he could.

And, of course — we have to mention that fight — the fatal third fight with Paret, would, by any standard, be the only real time on footage where Griffith truly showed what it looked like when he stopped pulling his punches. His recklessness got him in trouble multiple times against one of the most dogged contenders at welterweight, but Griffith enforced his conditioning, power, and accuracy to a terrifying peak that night.

Viewer discretion is advised for sections of the following clip selection. I did not choose the moments where the referee could have stopped the fight or the stoppage tiself for what I hope are obvious reasons.

Remember everything I’ve pointed out about how Griffith crafts entries, learns to control the inside game through his body position relative to his opponent, and how dangerous he is off the break? This above clip ought to inform what Griffith was like at his maximum gear.

Ultimately, if Griffith’s guilt led to him holding back, then I think I can believe that; I have yet to find him fight like he did in this bout. I’ve always heard statements of how fighters are “trained killers”, yet Griffith’s lifelong nightmares and accounts of grief ought to tell you that no fighter wants that title under any circumstance.

As a fighter, Emile Griffith was a competitor, and an extremely sturdy one at that.

The Middleweight Endeavor

In any combat sport, going up a weight class provides new dynamics, but the most obvious one is simple: you’re fighting bigger people. For Emile Griffith, to tackle Middleweight presented a challenge because these larger men were more equipped to handle Griffith’s strength up close and had the range advantages.

Griffith found his solutions at range. He mostly worked behind his jab to draw them into authoritative counters and lead hand jolts. It still led to many close wins, though his sheer horsepower and skill won him the respect of many esteemed middleweights, including Carlos Monzon himself.

Yet, one performance stands out: His title-winning victory over one of Middleweight’s greatest terrors, Dick Tiger. There’s a mantra among boxing aficionados and historians that Tiger was just about the worst fighter to try your hand in a firefight against. Even hellacious punchers and the grittiest of them all couldn’t afford that as he tore them apart like they were made of papier-mâché. Staying on the outside seemed the best bet, though Tiger was never out of answers — his pressure and pitch-and-catch counters made him a problem for anyone.

Griffith was a capable outside fighter, but losing his inside game — one of his strongest suits — seemed like it would cause his downfall.

That was not what happened. Griffith didn’t just engage Tiger on the outside — he outsmarted him on the inside too. Instead of conceding a single-phase fight, Griffith put together what may well be his greatest achievement: edging out Tiger in a fifteen-round affair for the Middleweight crown, where he put all of his ring smarts together for a complete showing.

One benefit to moving first behind your jab is that you force your opponent to follow you. When you jab or start moving in a different direction, you break their rhythm and force them to reset — this makes it easier to attack them out of position.

What happens when you hook off the jab? That makes the process more unpredictable because you can easily disguise jabs into hooks and vice versa. The opponent realizes you might be trying to draw them into a left hook, so they’ll look to cut you off or counter as you throw first. In Tiger’s case, he’s trying to look for a right straight or a cross counter. This is the trap Griffith sets:

Another reason hooking off a jab is useful? It’s incredibly easy to pull the punch back and transfer your weight into a right hand. And that same right hand counter times Tiger’s own to drop the iron-chinned former king to his knees for the first time in his career.

Seconds later, Griffith nearly pulls it off again: Tiger wants to keep Griffith in front of him? Griffith turns him. The hook draws the cross counter — and another right nearly takes Tiger’s feet out from under him while the bigger man’s counter has him standing square.

And, just when you can’t think Griffith couldn’t impress enough: he chooses to take on Tiger inside. Instead of a pure infight, Griffith waits until Tiger sets his feet or is resetting, and collides into him for the clinch. As dangerous as Tiger may have been on the inside: Griffith is at least his physical equal and even manages to push Tiger back on occasion. When he couldn’t do that, he made sure he could position his shoulders and head under or level with Tiger’s, turn him, and hit his trademark left hook off the break.

If there is one fight that demonstrates the consummate experience of Emile Griffith’s ring generalship and determination better, then you’d have to point me to it.

And, to think, Griffith still found himself competing for this same title over a decade later, well past the point most boxers would retire. He was genuinely too tough for his own good.

Conclusion

Emile Griffith is not the kind of fighter everyone is going to enjoy watching, though he may well be a fighter that you come to respect for how good he truly was. At his absolute best and past that, he took on every single opponent you could find and, at the very least, demanded the best out of all of them. Griffith’s style may well be an acquired taste for many fans of pugilism, though it’s undeniable that he was as tested and as great a fighter as you can find — only the best could and would beat him. You’d, likewise, be hard-pressed to find a fighter who was afflicted with adversary in and out of the ring as much as him and still showed nothing but class and humanity as him.

When I write these pieces, I genuinely attempt to avoid sentimentality, though you’ve probably noticed that it is in some abundance here. And I suppose it’s because I want to remember fighters for their sacrifices, accomplishments and qualities that we, as spectators, forget. At the end of the day, what these fighters choose to do is a competitive experience that we aren’t going to fully understand unless we are in their position. For me, I want to honor them for their greatness as much as possible. Emile Griffith is remembered as a great fighter, but it comes packaged with the commonly-stated factoid of “Griffith is that guy who killed his opponent”. The context is forgotten, the greatness is thrown aside — all that stands out is that Emile Griffith killed a person in the ring. And that’s going to be the first thing that people will likely see about him.

And that’s a shame. He was a lot more than that. And I think that a lot of his opponents and contemporaries would agree.