The All-Time Great Bantamweights: No 1: Rubén Olivares

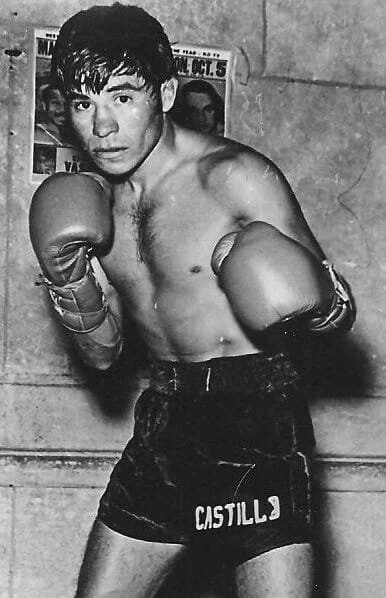

Ruben Olivares 89-13-3 (79 KOs)

If Ruben Olivares was a cartoon character his victims would be animated with their souls rising out and upwards of their bodies as they careened helplessly to the mat.

To watch Olivares hit his opponents gave the appearance not of a kids' cartoon but a gory horror flick; he would render them extras in a Zombie movie with a well-timed left hook or right cross. Their arms would drop, their legs would stiffen, they’d stumble in a waking dream, then drop like the undead after a shotgun blast to the head, unconsciousness a welcome respite from the nightmare of trading punches with the greatest Mexican knockout artist in boxing history.

Those lucky enough not to be knocked silly would be ground into dust by one of the most aggressive and well-balanced boxer-punchers that ever lived. If you cared for your vital organs, the bones that made up your cranium or the teeth you used to chew your food, you would do well to steer clear of the sweet science in the first place. If you were reckless enough to want to try a career in the fight game, you’d do even better to steer clear of Ruben Olivares.

Look at those numbers. Only ten men survived Olivares when he was in winning form. Padded? Nope, Olivares destroyed contenders like they were journeymen, he even crushed a fighter great enough to make this top ten.

Terry McGovern was a savage. Ruben Olivares was the greatest.

The Rise

The sheer amount of excellent Mexican fighters that sprung up in the 60s and 70s shows us what an excellent fight scene there was in the country, one that had produced world-class fighters before and all-time greats, but no truly great world champions. At bantamweight, Jose Becerra and Raul Macias had fleeting but impressive runs, and pound-for-pound ‘Baby’ Arizmendi and ‘Kid Azteca’ flew the flag.

Yet Mexican greats are often given the same knock that Greg Haugen put on Julio Cesar Chavez, that their records are built against Tijuana cab drivers (even if those cabbies are given credit for their toughness retrospectively) and even in this series the ninth-ranked bantamweight of all time - Carlos Zarate - got a bit of the same treatment from yours truly. But when looking at Olivares’ his superb run before he even challenged for a world title stands up to scrutiny.

He won the Mexican amateur championship but missed out on the Olympics, and with a style like his - and a life far removed from riches - the pro ranks were inevitably going to be roughed up by the boy who would be known in years to come as ‘Rockabye’ Ruben. Legendary trainer and manager Arturo ‘Cuyo’ Hernandez took Olivares under his wing, and the teenager from Mexico City would terrorise everyone he fought on his run to the championship.

It was a sprint along a road littered with broken bodies. Four years. 53 fights unbeaten, with one draw avenged by knockout. These are the numbers we are dealing with.

Jose Medel was a notable antagonist in the tales of no less than three of the great bantamweights in this top ten. In 1968 he was not in his prime but was still a danger to young prospects. He had recently put Lionel Rose on the canvas in a losing effort, and was less than two years out from giving Fighting Harada a tough fight in his second in a world title challenge. He was losing more often that not at this time (1-3-1 in his 5 bouts since challenging the great Harada) but had not been stopped since Eder Jofre put him down and out six years prior. Olivares stopped him in 8 rounds.

Octavio Gomez had beaten Olivares in the amateurs. He was a fledgling bantamweight with a reported 20-1-1 record when Olivares knocked him out in five. Years later, Gomez proved his worth by surviving Danny ‘Little Red’ Lopez (arguably the hardest ever puncher up at featherweight) en route to winning a ten-round decision. He also fought the likes of Eder Jofre, Rogelio Lara, Romeo Anaya and once beat the great bantamweight Rafael Herrera. He was one of many excellent Mexican bantamweights of the era.

Salvatore Burruni was as savvy and experienced a fighter as anyone plying their trade in ‘68. With an intimidating 94-8-1 record, the former world flyweight champion and reigning European bantamweight champion, Burruni was a broad shouldered Italian. Strong, skilled and knew how to survive. He had been stopped just once in his career, retiring due to an injury. He shipped a few left hooks from Olivares and turned his back on him, finding the whole experience so traumatic he refused to talk about it afterward. He never lost again, and retired as European champ, earning five more victories even after the shellacking Olivares gave him.

Tough Filipino Ernie De La Cruz dropped Olivares with a body shot in the second round before Olivares battered him to a ninth-round stoppage. Cruz dropped world champ Lionel Rose in his next fight and lost a tight decision. He was then stopped in ten by Chucho Castillo, before his countryman Ben Villaflor - a humongous super featherweight - beat him on points over ten, ending his world title aspirations once and for all. But he was clearly matched tough and was able to hang in there against world class fighters, so his giving Olivares a few tough rounds is no mark against the Mexican.

There were some talented Japanese fighters not called ‘Fighting’ Harada as well around this time. One of them was the great Masahiko’s brother, Ushiwakamaru Harada, who on film looks like a pale imitation of his great sibling but mixed it up with many bantamweight contenders. The pressure style is the same, but the nous, balance and speed his great brother possessed isn’t there.

Still, he was game, and provided an excellent canvas with which Olivares could splatter leather over, a superb Joe Louis-esque right uppercut-left hook combo sending the Japanese contender seemingly down and out. Ushiwakamaru may not have had his brother's skill but he had his heart, gamely rising and trying his best to fight back. He was saved by the referee in the second round, outgunned and outclassed.

Kazuyoshi Kanazawa was out of his depth when Olivares blasted him in two rounds. But we will meet him again later.

Undoubtedly the best of the Japanese contenders Olivares met in his early days was Takao Sakurai. Olympic gold medalist and one half of a highly-technical world title match with Lionel Rose, Sakurai was one of those weird beasts: a seemingly feather-fisted fighter who showed he could dig when it mattered most. He’d sat Rose down in his sole world title challenge, and he also put Olivares down when the two met in a world title eliminator in 1969.

A straight left was the shot which put Olivares down. The Mexican prospect claimed after the fight to be confused by Sakurai’s southpaw stance. This was an Olympic gold medalist, of course, a highly-skilled operator who had a 15-round world title bout under his belt.

In the small footage readily available of this fight, Olivares seemingly adopted the pressure style well known as a staple of Mexican fighters. Bearing that in mind, it was unsurprisingly body shots that won him the fight. Sakurai bravely rose three times from crunching blows that seemed to fold him in half. In the sixth, he could take no more, and Olivares had booked himself a meeting with Lionel Rose.

The ‘Oxnard Press Courier’ said that Olivares gave the finest showing of the night in dusting Sakurai, emerging as "a likely challenger but unlikely threat to world bantamweight champion Lionel Rose".

By the time they fought Olivares would be a slight favourite with the bookies. By the time the fight was over he would be a national hero.

Olivares vs Rose

Lionel Rose had already achieved enough at bantamweight to make the tenth place in this list. Nothing he did after he defended his undisputed world championship against Olivares got him there, for he never made the weight again. Thus, Olivares stepped into the ring at the ‘Fabulous Forum’ in Inglewood against an all-time great, the hardest way to win a world championship.

Rose had done the same, beating Fighting Harada in Japan to earn the strap, and considering that the successive bantamweight champions that held the unified title from Eder Jofre to Rose all featured in this top ten, you could argue that this was the strongest hand-off from great to great that any weight class has ever seen.

An op-ed in the ‘Van Nuys Valley News’ (California) saw Rose’s reign as such:

"Since then, of course, Rose has found a gold mine here in Los Angeles, where is becoming rich beating Mexican contenders. He got a good payday for whipping Jose Medel in a non-title fight at The Forum. Then came 70 Gs for his title defence against Chucho Castillo. Remember, the fight was close and ended in a riot."

That bout - in my eyes a classic contest - as well as the Medel ten-round fight, were looked at extensively in the essay that honoured Rose as the tenth greatest bantamweight of all time. But both fights were undeniably competitive. Both men could punch, both were Mexican, and both were excellent technicians, Castillo more well-rounded, Medel a peerless counter puncher.

Olivares was no less technical, although he was more ferocious and less measured than his compatriots. The same op-ed also felt that Rose’s luck would run out against Olivares.

Both men were 21, phenoms bang in the middle of their respective primes. A classic styles clash; the majestic boxer versus the danger man.

A ‘Sports Illustrated’ article shed light on Olivares’ personality outside the ring. He was a colourful character, but what seemed like a fun side to the monster that came out in the ring would prove a ball and chain around his neck as the years passed:

"Olivares is a relisher of bright clothes, shiny jewelry, soft lights and hard drink. He liked to go shopping. The last time he fought in Los Angeles he came with one suit of clothes and an empty suitcase."

Manager Arturo Hernandez was quoted in the same article. He said: “He’s homesick. All he wants to do is knock out Rose and go home."

George Parnassus secured his chance to stage the bout with an offer of $100,000 to the champion. An Associated Press report noted that Parnassus was hosting the fight on neutral ground, but that isn’t entirely accurate. The veteran promoter had staged many fights in California, and Rose was respected there. But Olivares, a popular Mexican, would have been the crowd favourite, and perhaps the owners of ‘The Fabulous Forum’ might have wanted to avert a repeat of the chaos that ensued after Rose beat Castillo on points if the bout went to the cards.

“Don’t worry about a riot," said Olivares, “I’ll knock Rose out within nine rounds”.

Olivares was not just a phenom but a prophet; Rose was out-gunned from the start.

Olivares baited him first, feinting with a jab to the body. Rose, savvy, defensively astute, didn’t bite. Olivares circled his man and jabbed with him. Rose had seen this before, the skilled Japanese boxer Sakurai who had dropped both him and Olivares giving him the same look. As he did then, Rose walked his man down, using his superior size to bully Olivares in close, chopping away with short jolts in close.

Rose might have had the larger frame, but Olivares was the stronger man. In a sequence that looks remarkably similar to Chucho Castillo downing Rose towards the latter stages of their fight, Olivares caught Rose with a right hand and sent him sprawling face first to the canvas.

Rose survived, but the following rounds saw Olivares amp up the aggression battering Rose to body and head, Rose’s reflexes first clawing back the space and time he needed to survive, then dulled by the debilitating body blows that Olivares dug into him.

Stunned by this, his legs sapped from underneath him, the once slick Rose was reduced to a large target for Olivares to tee off on. Down twice more, his trainer Jack Rennie, who loved him like a son, jumped into the ring to save him from further punishment. Olivares had got the job done in five rounds, quicker than even he had predicted.

Rose, always classy, had nothing but good things to say about the man who had smashed him down and taken his belt from him;

“He’s a great bantamweight," said Rose, quoted in a ‘United Press International’ report the day after the fight. “But the bantamweight division is hotly contested and the title is very hard to hold. Olivares will find that out but if he’s the fighter I think he is, he could hold the title a long time."

Rose was also quoted by ‘Sports Illustrated’, where he went more in depth as to why he lost the bout: "He kept hitting me under the rib cage," Rose said, "I couldn’t get my breath."

That certainly explains why Rose didn’t move around as much as usual, which in turn left him exactly where the Mexican wanted him to further his body assault.

Although Olivares had landed his left hook early and dropped Rose in the second, he was obviously still respectful of the former champ’s talents, simply saying, “in the middle of the third I knew I was boss”.

And the boss of the division, a weight class which Rose rightly said was a tough one to remain the boss of for long.

There was only one thing on Olivares’ mind after the fight, and it wasn’t continuing his legacy.

“Come, vacation with me, Acapulco. Great time, great place! Come, I treat you to the works-wine, women, song.”

While this pattern would repeat during Olivares’ career, he gave the wariest of his camp some encouragement.

“Do not worry," said Olivares, “I know when to work and when to have fun. Before the fight, I sweat. Now I play.”

Olivares would play in the ring as much outside, the canvas his sandbox, continuing that great lineage of champions; Jofre, Harada, Rose, and now Olivares.

All had lost their titles in the ring, even when the illustrious featherweight division beckoned. Defending their hard-earned championships seemed to mean more, even in the face of heinous weight cuts and a murderers' row trying to knock the crown off their heads.

Rose himself had struggled with the weight. In fact, he never fought at 118lbs again, a young pup when king and finding the throne uncomfortable to sit on as he filled out.

Against Harada, he put forth one of the best exhibitions of pure boxing skill within the confines of the weight. Against Jesus ‘Chucho’ Castillo, he was one half of a truly great world title clash.

Against Olivares, he was on the receiving end of arguably the worst beating suffered by an all-time great in his prime at the hands of another.

Fellow boxing historian Matt McGrain, writing for ‘The Sweet Science’, summarised Rose thus when ranking him sixth in his own countdown of the great bantams:

"Perhaps a little unfairly I would identify Rose as the weak link among these four great champions; but this is a little like identifying Ringo as the weakest member of The Beatles. It’s better being the worst musician in the greatest band ever to have played than the best musician in your mother’s basement."

To take the analogy further, if Rose was Ringo then Jofre was Paul; versatile, measured, respected. Harada was George, affable, well-loved, with a resume that only gets more impressive the deeper you look.

Olivares then, was Lennon. The badass of the bunch, violent, unpredictable.

In his first defence, Olivares would take on another excellent bantamweight, and unlike the analogy posited above, he was actually given the moniker of ‘The Boxing Beatle’. Like Jose Medel, Alan Rudkin has featured prominently in our look at other members of this top ten, a terrific fighter whose ability to give the greats a tough test only adds to their legend.

He features in the tale of Ruben Olivares too. What the Mexican did was not only more impressive than those legendary bantamweights, but terrifying.

The First Defence

Alan Rudkin had won two bouts following his razor-thin decision loss to Lionel Rose, defending his British title once and scoring a quick first-round KO in an over-the-weight bout. By all intents and purposes he was still the contender who had put forth a solid case to be christened the main man. He had also taken the great Fighting Harada the distance. He was quick, unnaturally tough and could box as well as he could scrap, and as a scrapper he was without equal even in these deep and dangerous bantamweight waters.

Thus he was as surprised as anyone when Ruben Olivares was installed as firm favourite over him, reportedly laughing at the bookies.

"Olivares is a puncher and a comer. What I mean is that he will come to me. I won’t have to chase him. I like that type of fighter. You will see I can stand my ground and fight too," Rudkin told ‘The Liverpool Echo’.

Rudkin had the ghosts of world title fights past in his head though, and was concerned about how the fight might go if it went the distance.

“I’ve lost twice for this title, and both times I was the victim of a hometown decision," he said. “So this time, I’m going out to knock out Olivares, and I am sure he is going to try and do the same to me."

Rudkin did as he said, taking the fight to Olivares early, perhaps hoping he could push the champ onto the back foot and dampen his power.

Rudkin’s manager Bobby Neill told the ‘Liverpool Echo’ that Alan had decided to have a go at Olivares, adding, “It was against my advice."

Just as in the first round against Harada, Rudkin found himself on the deck, a "stinging left hook" doing the damage. Reports said this was the first time Rudkin had been down, not quite accurate but then the knockdown against Harada seemed as much a product of tangled feet as it did a good punch.

In the second round, Olivares rammed a right hand into the pit of Rudkin’s stomach that had him on his knees gasping for air. Rudkin fired back with a right to the heart, but Olivares had a whiff of blood and was impossible to stave off. A left hook flattened Rudkin with 30 seconds left in the round. He was out.

“I have never been hit so hard in my life," said Rudkin, knocked out for the first and only time in his career. “All of a sudden I found myself sitting on the canvas. I don’t even know how it happened."

Olivares blasts Rudkin

Rudkin also weighed up Olivares against the previous greats he had faced: “He is a much better fighter than the other champions I fought, Lionel Rose and Fighting Harada in all regards. It would have to be a real good puncher to slow him down.”

An ‘Associated Press’ report said there was "no competition left in field" after Olivares dismissed Rudkin. This was how he was perceived at the time, as having cleaned out the division in just two world title bouts.

There were other challenges out there though.

The ‘Liverpool Echo’ saw it like this:

"Meanwhile, back in Mexico, they will be developing another mighty midget to let loose on the boxing world. They say that good bantams grow there on trees and Rudkin will certainly subscribe to this theory. Mexico also produced Jose Medel, who stopped Walter McGowan in six rounds; Jesus Castillo, who stopped Evan Armstrong in two - and that accounts for Britain’s three top-ranked bantamweights - and the incomparable Vicente Saldivar, who beat Howard Winstone three times and probably still gives him nightmares. On reflection, perhaps we would do better to let these swarthy little men fight it out among themselves."

This demonstrates how the 60s were truly the golden age of Mexican boxing. Dangerous and skilled contenders and champions spread over the lighter weights, not just defining Mexican boxing for the era, but for the rest of all time.

Olivares fancied taking a chance at the two titlists up at featherweight, either boxer-puncher Shozo Saijo of Japan, or tough pure boxer Johnny Famechon of Australia.

A Mexican writer instead called for Olivares to defend his title against one of his own.

“I prefer to fight guys other than my countrymen," is what he reportedly said in response to that question.

The number one contender had fought on the undercard and came out victorious. Much to Olivares’ chagrin, he was a compatriot. As Rudkin called for, he could punch. And when Olivares’ fighting pride got the better of him, he would be the man who would define Olivares’ career.

The Chucho Castillo Trilogy

Let’s roll it back. Not to the beginning of Olivares’ career, but to the lower end of this top ten.

When I started writing it, Chucho Castillo sat proud in eighth place. Above Lionel Rose, who he had that closely contested loss to. Above Carlos Zarate, who in most lists sits among the gods in the top five. Above Panama Al Brown, who eventually took Castillo’s spot.

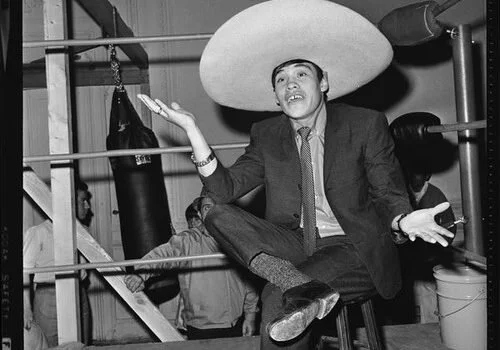

The great ‘Chucho’ Castillo

I did not discover anything about Castillo that made him fall a few spots and out of the top ten. I discovered he was much as I thought; a truly great bantamweight. That he just missed out is not an indictment of his quality as a fighter. The lower half of the top ten was just that hard to call, much as I have found the top five to be.

In simple terms, without Jesus ‘Chucho’ Castillo, Ruben Olivares might not make the top five of this list, let alone be standing on top of the mountain, fists clenched, ready for any potential usurpers.

Castillo had gone 5-1-2 since his riot-causing loss to Lionel Rose, drawing with Jose Medel (who he held a win over) Ushiwakamaru Harada (who Olivares had stopped) and going 1-1 with top-notch Mexican Raul Cruz.

But the jewel in the crown of this run, which may look more impressive numbers wise when you consider it was in the space of a calendar year, was a third-round knockout of Rafael Herrera.

Then just a domestic rival, Herrera would eventually become the third of the holy trinity of Mexican bantamweights. And while Boxrec lists it as a simple ‘TKO’, Herrera himself was much more honest in his summary of the bout when talking to Dan Hanley for ‘The Cyber Boxing Zone’ in 2012.

Hanley asked whether Herrera had been stopped on a cut:

"This fight was for the Mexican bantamweight championship and Castillo was the number one contender in the world. I took this fight very seriously and thought that if I could beat Castillo then I could actually beat world champion Lionel Rose. But, there was no cut. This was the first fight that I was actually knocked out."

So Chucho Castillo was about as good as it got during an era where the bantamweight division was as good as it got.

When the men finally met to sign the contract, they started their civil war earlier than expected.

“Olivares is weak on defence and he has never had to go 15 rounds," said Castillo. “If it goes into the late rounds, I should beat him."

Olivares, no stranger to showing his colourful character, fired back in kind,

“There is room in Mexico for only one champion. And I intend to show I am the champion of my own country as well as the world.”

Reports claimed they didn’t like each other. They had fought on the same cards before, and with one unified champion and one true number one contender it is not hard to see why these two proud Mexicans resented each other.

‘Sports Illustrated’ saw Castillo and Olivares’ reasons for their mutual hatred;

"When Castillo became the champion of Mexico in 1967, Olivares challenged him. Castillo told him that he would have to wait his turn. Finally a fight was set, but when Castillo was given a shot at Lionel Rose's title late in 1968, Olivares was again told to wait. 'He knows I'll beat him,' said Olivares. When Castillo lost a controversial split decision to Rose, Mexico almost severed relations with Australia. The Mexican fans who were crammed into The Forum in Los Angeles that night rioted for over an hour. 'Why all the fuss?' said Olivares. 'Rose won. I was surprised the voting was that close.' Ruben didn't win any popularity contests in Mexico after that. Then stories circulated that Olivares was paying more attention to tequila than to training, and he became even less popular. Mexicans expect their boxing heroes to become drunks. It's something of a tradition. But they want them to wait until they retire."

Olivares might have been continuing with a steady training regime of gym work and partying, but the champion at least knew the qualities his top contender possessed:

“I know Castillo will be my toughest opponent because our national pride will be at stake in this fight”, Olivares said. “Castillo is a very determined boxer. I think he will give me a better fight than Lionel Rose did when I won the title, even though Rose beat Castillo."

Olivares also told the press that due to Castillo’s physical strength and punching power being superior to that of Rose he had not been cutting corners in training.

He had been to Disneyland in the days leading up to the fight. Olivares couldn’t resist extra curricular activities, even if he wasn’t up to his usual partying.

Castillo summarised his training camp thus: “I’m not going anywhere except to the gym and the [Inglewood] Forum." The challenger was a no-nonsense fighter.

Before the fight, Olivares’ record was lauded with terms such as ‘unbelievable’, due to his astonishing unbeaten ledger and his ginormous list of knockouts. His confirmed record going into his first fight with Castillo was 57-0-1 with 55 knockouts. He had knocked out every man he had faced, bar one who was saved by being disqualified instead, and had shown himself a man sure to tie up any loose ends with anyone who dared take him the distance. He had avenged that draw too, by knockout of course.

Castillo’s training was interrupted by his son falling ill in Mexico, but he returned to the United States, the bout not being postponed as a result. A month before the bout his father was killed in an accident.

“He has always been on the quiet side," said Castillo’s manager Geronimo Lopez, “but I have never seen him like this. He has been in a dark mood and refuses to see anyone."

Castillo still obliged reporters who asked him about his opponent:

“I’m only interested in beating Olivares”, he said. “It is all I live for. Olivares is a loudmouth and not deserving to be champion. In Mexico, I am the popular one. I will beat Olivares and then the title will truly belong to my country."

Castillo was also banking on a chink in Olivares’ armour. He wouldn’t disclose exactly what it was, only that it was, “a big mistake I can take advantage of”.

Olivares said he would stop Castillo inside of two rounds.

The stage was set for a grudge match between two bantamweights at the peak of their powers. Both could punch, and both were technical. The champion had never tasted defeat, the challenger had and had come out better for it.

Olivares was making $100,000, the same price Rose set when he was champion. Mexican television rights were reportedly $75,000, astronomical for a bantamweight fight in those days. The Inglewood Forum was sold out, and readers of the ‘Van Nuys Valley News’ were told to check out the theatres showing the bout as getting a ticket was impossible.

Olivares vs Castillo had been billed as ‘The Mexican Civil War’. The fight lived up to its billing.

Olivares vs Castillo I

Both men feinted and prodded their way in. Characteristically Castillo took the back foot and Olivares was the aggressor. The champion got off first, bringing himself closer to Castillo with whichever hand was closest and bringing the opposite hand into play, catching the challenger off guard. But after two rounds Castillo had barely flinched, despite tasting leather more than once.

In the third Olivares stepped in again, but instead found himself down, a short counter right hand his poison. Was this the mistake Castillo claimed to have seen? Olivares sprung up immediately and tasted another right hand for his troubles, all before the referee could start the count.

Olivares proved Castillo wrong on a few counts. The opening Castillo saw was not Olivares’ downfall. Castillo hurt Olivares again in the 14th round, but found Olivares capable of slipping shots. The champion showed the ability to counter punch as well as the master.

And at the end of 15 rounds - where the challenger had predicted Olivares would be at his weakest - the champion retained, working hard after the knockdown to keep the pressure on Castillo and landing the more quality punches. No mean feat when faced with a master counter puncher like Castillo, who was competitive throughout.

Olivares had shown he was not just a front runner; he was of championship calibre and could defend his title over the distance against a highly-skilled fighter. Castillo had taken the champion's best punches and not come close to folding, yet Olivares had shown poise and a good engine.

Both men seemed to have lost none of their distaste for one another after the fight, but had gained a newfound respect a fighter only earns after bravely withstanding the other for 45 minutes.

“Only two other men have gone the distance against me and tonight was the first time I’ve ever gone 15 rounds. I don’t like Chucho, but he’s not a bad little boxer," said the champ.

“I knew he was good, but thought I was better," said a disappointed Castillo, adding that Olivares’ left hand was "positively the best I’ve ever seen…and felt".

Castillo called for a rematch.

“And he can have it," spat Olivares, as quoted by ‘Sports Illustrated. “He’s a good tough fighter and he gave me my toughest fight. He was in the super condition of his life. That’s what held him up. And he’ll never again be able to get into that kind of condition."

Olivares vs Castillo II

Olivares made no more defences between his fights with Castillo, instead fighting as a fully fledged featherweight for three bouts (3-0, 2 knockouts) while Castillo took on a stiffer test in defence of his NABF bantam title, beating yet another hard-punching Mexican Rogelio Lara by 12-round UD on a stacked card at the ‘Fabulous Forum’ which also featured Olivares in one of his featherweight bouts and welterweight great Jose Napoles.

Olivares was on hand for the Castillo vs Lara bout, and predicted an easier win second time round.

With Lara out of the picture, Castillo - still the number one contender - was granted his rematch, and was said to be "ripping into his sparring partners like a man getting ready for a do-or-die effort".

Castillo’s manager ‘El Conjo’ Lopez said his charge was approaching the rematch differently:

‘We boxed him last time and we lost. It was a case of block and punch and it was no good. This time will be different. It will be punch, punch and punch again, and Castillo can punch. Remember, he scored the only knockdown in his first fight with Olivares."

On the flipside, Olivares’ training sessions had some onlookers worried.

"The meanest 118lb hombre, this side of, well anywhere, is risking his crown tonight at [Inglewood] Forum against Chucho Castillo and the champ has looked bad enough in workouts that the odds have dropped him to only a 6-5 favourite."

"I’ll be ready tonight," said Olivares. "I saw something in the first fight and will score a knockout."

Olivares had predicted a stoppage in his first fight with Castillo, and it hadn’t happened. In fact, he had been the one on the canvas. One report labelled Olivares as happy-go-lucky. He was not concerned about his opponent.

As is in their first go, Castillo was seen as more introverted and serious. He was said to have looked solemn, and confided to his team that he would have to knock Olivares out to win.

The ‘Press Telegram’ asked Castillo to delve into his feelings on Olivares. Time had not been a healer:

"I laugh at him," said the challenger. "He makes me sick. In our first fight I had the only knockdown. I felt so strongly against him that I almost wanted to smash him again the second he got up. I went the whole 15 rounds with the guy before. So what makes him so great? Nothing. Have you seen him lately? He looks like a bum."

Hank Hollingworth, writing for the same publication, went on to describe why the bout was not just important for the fighters involved, but for the sport of boxing:

"The bantamweight championship is something sacred within itself if for no other reason that it involves MORE outstanding fighters than any other boxing division. Look at the heavyweights, for instance. Even somebody like Jerry Quarry has a chance for the title. Don’t even mention the lightheavies. A student of the game could go even further."

It is true that bantamweight has historically been a deep division full of killers. And that the unified championship came down again to Olivares and Castillo - the bona fide number one and two - speaks of the magnitude of this fight.

The result arguably made it even more special.

The first few rounds looked much like the first fight; lots of probing, feinting, trying to create an opening for a heavy blow. Olivares tried to go over the top with a right hand; Castillo responded with rights of his own, showing Olivares he was the master of that particular shot. Both men commanded centre ring and pawed with their jabs. Even without much to write about here, it remains a pleasure to watch these two masters.

Only one thing of note happened in those first few rounds, and the grainy footage doesn’t shed any light on how it occurred. The fighters and onlookers also seemed to disagree. But whether caused by leather or bone, the champion was bleeding.

"I hit him with a right hand punch," said Castillo, a case which is certainly supported by the film. Both the referee and Olivares saw a headbutt as the main factor.

It changed the course of the fight. Olivares was his usual brilliant self but Castillo - as was reportedly his game plan - became the hunter. Both men exchanged punches in close in an engrossing battle of aggressive counter punching. Unlike the first bout, Olivares remained upright throughout. Castillo opened another cut underneath the eye with a right hand later on and try as he might, Olivares’ experienced trainer ‘Cuyo’ Hernandez could never stop the wounds from oozing.

But he was stopped, the contest halted in the 14th round when the crimson mask Castillo had gifted him turned opaque.

Referee Dick Young explained his reasons for stopping the fight:

‘It all started in the first round. Both men came together real hard and they butted heads. Castillo came out all right but Olivares had a slit over his left eye. He also incurred a cut on his left cheekbone. The doctor thought it wasn’t necessary to end the fight, so I went alone with him. It was bloody and messy in the ninth round but I saw no reason to finish the fight then, either. After all, it was for the title. However, in the 14th round, I had to stop it, as much as I didn’t want to."

The ‘Associated Press’ report gave credit to Castillo’s strategy, seeing him as "the expert in the later rounds in banging the body to bring the guard down and then sharpshooting the wounded eye".

The new champion said after the fight he knew this was his last chance to win the title.

"I think my combinations affected him," said Castillo. "I didn’t use many combinations in our last fight and he didn’t expect them this time."

The now deposed champion was indignant and played down Castillo’s efforts.

"Castillo didn’t fight me any different this time than last time, except for the butts."

This doesn’t ring true based on the footage. The first fight was a boxing match, and although no less technical, Castillo threw many more punches, and was more aggressive. Olivares accommodated him, true, but the words pre-fight from Castillo and his camp gave Olivares a strong clue as to his opponent's tactics. In the ring you see things differently, of course, and interviewing a fighter after losing his ‘0’ and his championship might not be the best time to get an accurate analysis of a fight.

Not that Olivares hadn’t fought well. Although there were concerns about his training camp leading up to the bout, he had met Castillo’s punches with his own and protested the stoppage. In the 14th round, one judge had him up, with the other two ruling it a draw. The champion had not been exposed, he had merely met the one challenger who was his equal technically and who could stand up to his punches.

The two best bantamweights in the world were now one apiece. You know what happens next.

Olivares vs Castillo III

"I only loaned Castillo my title and I’ll win it back by knockout within nine rounds."

It was the champion Chucho Castillo that first called for a rubber match, and hoped it would be held in Mexico City, but the Inglewood Forum was big business for George Parnassus and the previous two fights between them had sold it out. Both men took warm-up fights (both scoring early stoppages) and six months after their brutal, bloody rematch they met again.

Olivares was obviously confident of winning. But Castillo, once quiet, sometimes surly, seemed to lighten up despite the gold weight around his waist.

"I must be improving," he chuckled. "Last time Olivares said he’d finish me in six rounds."

Castillo was not resting on his champion status. He was said to be training hard, and even received a few pointers from the great ‘Sugar’ Ray Robinson. He was confident and assured, as always. The only thing that annoyed him?

"Why Olivares, why Olivares?" he asked. When pressed, he just repeated the question.

"The situation is this: Chucho Castillo may be the champion, but Ruben Olivares gets all the publicity", wrote Dan DeLong for the ‘Pomono Press Bulletin’.

Olivares might have looked past Castillo in their second fight, but his bravado could not be underestimated even after losing his title. He had told promoter Parnassus to line up world featherweight champ Kuniaki Shibata as soon as possible, he was that confident of winning back his title. The veteran promoter told Olivares to keep his mind on the task at hand.

Both men appeared to be in superb shape for their important rubber match. Dr Jack Useem of the California Athletic Commission said, "These two little fellows are two of the best conditioned athletes I have ever checked", at the pre-fight medical. Neither was leaving anything to chance.

Olivares might have been training hard for Castillo as well as having his eye on a title in a second weight class, but there was one thing he always had his other eye on.

Dan DeLong again: "Olivares is always busy with the ladies or something else. Sometimes he’s at the track, or walking through Mexico City, where Olivares is a hero, but it’s always back to the clubs and the ladies."

Not that Olivares’ ability to fight wasn’t what mostly kept him in the headlines.

One report said, "Boxing experts consider the muscular native of Mexico City as the best puncher the bantamweight division has ever known." Certainly a case can be easily made for Olivares in that discussion, but his rubber match with Castillo further demonstrates his placing here as the greatest all-round bantamweight of all time.

For in this fight, an almost carbon copy of their first meeting, Olivares showed resolve, adaptability, and a level of ring generalship not normally associated with pure punchers.

In another callback to their first fight, he also had to drag himself up off the deck to do it.

Castillo had played matador in the first fight, and the second saw him the bull with Olivares’ face the red rag. In this one, Olivares went against type, showing himself capable of a disciplined boxing performance, forcing Castillo to come to him.

Not that Castillo’s counter-punching abilities had disappeared upon him winning the title. Olivares got too eager in the sixth round and was sent down by a counter left hook. Castillo showed again that he was also a two-fisted puncher.

Olivares had battled through the blood when losing the title, and here he regained his composure as quickly as the mandatory eight count as registered. He fired off single shots and slipped under Castillo’s return fire, spun off and regained centre ring. He didn’t stay too long on the inside, and forced the counter puncher to follow him around.

In the 13th when the champion desperately tried to turn the tide he was met with a series of thudding body shots. At the end of 15 rounds, Ruben Olivares once again was world bantamweight champion, his jab and movement the difference in a decision that all reports saw as one-sided.

"I was never worried during the fight," said Olivares in his dressing room after the fight, flashing his signature toothy smile. "I was completely confident."

Castillo said he would be happy to meet Olivares again.

The ‘Associated Press’ report said there was no need. In winning the trilogy, Olivares had "slugged himself out of opponents".

This wasn’t quite accurate. But Olivares would never again box with the same verve and panache that he demonstrated in his third fight with Castillo.

Within a year he had been knocked out and lost his title for good.

The Final Three

When looking at Olivares’ early days I said we would meet Kazuyoshi Kanazawa again, and in Olivares’ penultimate successful defence the Japanese battler was the opponent.

Kanazawa was never the most consistent fighter, but he nailed some impressive scalps to his wall; tough Thai Berkrek Chartvanchai had recently held half of the world flyweight title, he survived an aging Jose Medel for ten rounds, and opened a nasty cut around the eye of dangerous Mexican Jesus Pimentel for a ninth-round stoppage win.

He had suffered stoppage losses to Ushiwakamaru Harada and future bantam titlist Rodolfo Martinez (as well as being blasted by Olivares in two rounds) but was 3-0 in 1971, winning the vacant Orient bantamweight title.

Olivares was said to be working hard and not counting out Kanazawa based on their previous meeting, but judging by the footage that seems hard to believe. Olivares seemed to be leading with power punches with little set up for much of the fight, and this coupled with the brave Japanese trying his hardest to win the title saw Olivares get himself into some bad spots.

Olivares’ attempts to put Kanazawa away saw him put down, half by a counter left hook, half by a shove. It was ruled a slip, but to my eyes looks a legitimate knockdown.

Later on in the fight, Olivares put forth a more educated effort, pressuring the challenger with his patented body shots. But in the 13th round Kanazawa exploded into a two-handed flurry which had Olivares stranded against the ropes, referee Jay Edson having more than one close look at the champion.

Kanazawa, tired at unloading his full arsenal on Olivares, threw a series of wide punches that a blind man could’ve easily avoided, and missed one flailing punch so badly he ran halfway around the ring and fell over. This gave Olivares some respite, and in the 14th round he upped his game, brought more pressure and Kanazawa flopped to the floor repeatedly, enough times that the bout was brought to an automatic end.

Olivares credited the challenger for his efforts, telling ‘The Pacific Stars & Stripes’ that he was a much improved fighter.

Kanazawa, who received much acclaim from the Japanese crowd for his brave efforts, had no regrets.

"I did my best," Kanazawa said. "Olivares was too strong for me."

Olivares would make his last successful defence back in Inglewood. His opponent, a perfect one, Jesus Pimentel, who has been a staple of this series despite never being in a world title fight.

In fact, he had been threatening a challenge of Eder Jofre, Fighting Harada and Ruben Olivares since the early 60s. His manager Harry Kabakoff seemed to seek more and more favourable deals for his man, and the fights inevitably fell apart. Lawsuits and dirt-slinging would ensue (often from both sides) and Pimentel would invariably go on another run of knockouts against outmatched opposition.

By the time he came to challenge Olivares, he was past his best. Gone was the undefeated terror of the bantamweight division, and in the opposite corner Olivares would see a battle-scarred man who had lost three bouts in three years.

That doesn’t sound like a particularly bad run. But when you consider that Pimentel had failed to outgun Kanazawa, been widely outscored by Chucho Castillo, and outworked by unheralded Filipino Bernabe Fernandez, the cracks in his game were as visible as the scar tissue on his face.

But Pimentel had drummed up interest in another big fight in his own inimitable way, racking up 15 wins in succession, 13 of them inside the distance, not one of them against a first-rater.

On a bill that also featured Jose Napoles defending his title against the underrated Hedgemon Lewis, promoter George Parnassus felt it was the ‘biggest’ of his career (although as one writer put it, the promoter almost always put out a quality product).

There was a rumour before the fight that Parnassus would gift the champion a brand new Cadillac if he won within five rounds. When the promoter scoffed at that idea, Olivares said, "If I don’t get the car from someone I intend to buy it myself."

Pimentel was first slated to challenge Olivares a year earlier. Olivares instead gave Chucho Castillo a rematch, and it will be no surprise to anyone that has read Eder Jofre and Fighting Harada’s installments to discover that Pimentel and his team tried to sue Olivares.

Even then, Frankie Goodman writing for ‘The Van Nuys Valley News’ in California predicted that Pimentel would be stopped in quick fashion if he were to challenge Olivares, adding, he "would be no match for the champion at this present time".

Pimentel seemed to acknowledge this before the fight.

"I feel real good," Pimentel told the ‘Associated Press’ reporter before the fight, adding in defeatist fashion, "but I’ve got to understand that years have passed."

But two Mexican knockout artists guarantees an interesting fight even if it transpired as to not being all that competitive. Olivares and Pimentel had over a hundred knockouts between them.

Olivares didn’t get rid of Pimentel within five rounds, but he boxed beautifully after being cut in some ferocious early exchanges. Realising Pimentel’s best chance was in a fire fight, the champion got on his toes, displaying more poise and intelligence than he had in his previous defence and harking back to his third fight with Chucho Castillo.

In the sixth he nearly got the stoppage, sending Pimentel half out of the ring. But after waiting so long for a title shot, the challenger wasn’t going to give in that easy, and fought his way back into the fight. Pimentel got his licks in, but Olivares was the general, and Pimentel’s loving manager Kabakoff pulled out the veteran at the end of the 11th round, knowing there was nothing his man could do to turn the bout in his favour.

"He didn’t get the car," said Pimentel after the fight. "Father time - you just can’t beat him", Pimentel added, before retiring. He stayed true to that decision, ending his impressive career with a 76-7 record, and an astonishing 68 KOs to his name.

"Pimentel has a lot of courage," was all Olivares said of his challenger. "Guts."

Guts are synonomous with Mexican fighters. Pimentel’s had been called into question before, but in the twilight of his career he had put forth a spirited effort against a fighter who was essentially a younger, bigger and better version of himself.

But his tendency to pull out of fights meant another Mexican was on standby lest Pimentel come down with a phantom illness before the fight.

Three months later, Rafael Herrera would be rewarded for his patience. Olivares would be punished for sticking around for too long, thoroughly outboxed and then flattened by a short left hook in eight rounds.

It begs the question: why not Herrera?

The G.O.A.T.

The first fight between Olivares and Herrera could be seen in some ways to be the perfect ending to Olivares’ time atop the bantamweight division. His last win at the 118lbs limit came against another legendary Mexican puncher, Jesus Pimentel, in his adopted home of California. And he lost his title to another Mexican, back home in Mexico City, his prime ending where it all began. The torch had been passed, or rather taken with thunderous punches.

Unlike Olivares’ previous loss to Castillo, there was no bad blood between these two Mexican warriors.

"I’m sorry I beat you," said Herrera to Olivares, "But I need the money."

Olivares was listless in this fight. Sluggish, his defensive radar seemingly switched off, and swinging wildly with his punches. On film, it looks a lesser performance than he mustered against Kanazawa in Japan, and in Herrera he was faced with a bantamweight of the highest calibre. At home, in a domestic dust-up in defence of the title he worked so hard to win back from Chucho Castillo, and yet Olivares was as poor as Herrera was great.

Herrera took nothing for granted and remained respectful of Ruben’s talents.

"They all hurt," he said, when asked if Olivares’ punches had any effect on him. "I was thinking [of a knockout] but you can never be sure of that with Olivares," said the newly-minted world champ. The new champ said he had no game plan, but rather waited to see what Olivares would do and adapt in turn.

Yet after such a shocking and one-sided defeat, Olivares reacted strangely. He was smiling as soon as he got back to his dressing room. He gave the new champ his props, and the ‘United Press International’ post-fight report said Olivares seemed relieved the fight was over.

Or perhaps that his cut to bantamweight was over? After the fight, Olivares signaled his intentions yet again to move up to featherweight, following the same path as Eder Jofre, Fighting Harada and Lionel Rose before him, squeezing himself into the bantamweight limit until he couldn’t any more instead of leaving the division with his title.

Herrera had beaten Olivares in a fashion the now former champ could be proud of. But his reign did not reach the level of Olivares’ despite this win, which on film holds up as one of the best victories in the division’s history.

Herrera was also the last ever unified bantamweight champion: he lost his belts in his first defence against Enrique Pinder away from home in Panama. Pinder was then stripped of the WBC portion of the title, which Herrera picked up, and made three defences: two of them impressive, against fellow Mexican punchers Romeo Anaya and Rodolfo Martinez, and one of them dubious, in which Thai powerhouse Venis Borkorsor seemed to punch out a decision but found himself leaving empty handed after 15 rounds. Herrera suffered such horrendous facial injuries in that fight his wife said his appearance scared children afterward.

Rodolfo Martinez then stopped Herrera in four rounds, and the man that knocked out Olivares never won a title again. His pre-prime run, his short title run and his win over Olivares put him in contention for a spot in the top ten. But unlike Olivares he never distinguished himself over Chucho Castillo. He avenged the aforementioned KO loss with a tight decision win over 12 for the NABF title, not nearly as impressive a performance as Olivares in his third go with Castillo. Herrera’s title run was impressive but not astonishing. He was undeniably great, but not the greatest.

There is a case to be made that Herrera was a bad match-up for Olivares. An over-the-weight rematch was closer, but Herrera prevailed again over ten. But this is to be expected in a stacked era. To use a modern example to illustrate my point as succinctly as possible, you would struggle to find many boxing people who would rank Juan Manual Marquez higher than Manny Pacquiao on their all-time lists.

Like Pacquiao and Marquez, Olivares took his talents up in weight as he promised. His career was a mixed bag after that, boasting impressive wins over Bobby Chacon (2-1 in a trilogy), future lightweight champ Jose Luis Ramirez (KO2), and winning the WBA featherweight title.

But up in weight, the dominating master of old was replaced by a sometimes vulnerable, undersized and past-prime puncher who could run out of gas trying his darndest to get the job done. Art Hafey pole axed him in five, Eusebio Pedroza picked away at him in 12, and when the super bantamweight division was created Olivares fell apart in an eliminator. That division was created too late for Olivares, who likely would have been perfectly built for 122lbs.

Perhaps his most famous fight is a defeat, a 14th-round battering from the legendary Alexis Arguello after a Herculean effort from Olivares in which he demonstrated much of the pure boxing and counter-punching ability he had dished out to Chucho Castillo in their rubber match.

Olivares lost his half of the featherweight crown that night, and never wore a belt again. Today, he runs some businesses and appears to have all his faculties. That trademark style can still be seen on the streets of Mexico City or at boxing conventions. From his appearance, Olivares appears happy and to be living well, a great thing as he was in many wars during his career.

But back to bantamweight, and those prime years. It’s no accident that Rafael Herrera and Chucho Castillo barely missed out on the top ten. And it’s no fluke that Lionel Rose sat pretty in tenth place. In order to be great you have to share the ring with the best possible opposition.

And more often than not, Ruben Olivares destroyed world class opposition, winning 61 fights before someone figured him out, and with six successful defences of the legitimate, unified world bantamweight title he beats out Fighting Harada and Eder Jofre for numbers.

Manuel Ortiz had more, but as I pointed out in the piece that argued Ortiz was fairly ranked at number six, sometimes numbers only tell half the story.

Olivares has the great Ortiz beaten on the quality of his opposition. And that, at least in this list, is the single most important criteria.

Do not think for a second that this list favours punchers. With Terry McGovern and Ruben Olivares in the top two spots - two fighters who coincidentally had very similar career arcs - you may think you have me figured out, but I can assure you there is no bias towards bangers.

If this top ten demonstrates anything, it’s that the bantamweight division has hosted arguably the most diverse array of stylists, some of the hardest pound-for-pound punchers, and some of more classy technicians and some of the greatest pound-for-pound fighters of all time.

Ruben Olivares ticks every box.