Fast And Slow: A Look At Cody Garbrandt

Photo by Mike Stobe/Getty Images

In a lot of ways, the idea of a fighter being “limited” is somewhat misunderstood. The best way to put it is that “well-roundedness” is often not a good thing, and this was clearest in the advent of fighters like Rory MacDonald, whose point of uniqueness was that he started as an MMA fighter and therefore didn’t have the weaknesses that those that started in other disciplines did. The problem was that he also didn’t have the strengths, and so when Robbie Lawler boxed him into a boxing match, MacDonald was stuck in a place where he was fine but his opponent was excellent. In general, the best fighters (sans the best of all time, like Jose Aldo) have areas of weakness, they just also have areas of strength into which they funnel the fight.

Where many specialists struggle is in that funneling process, where they can’t get the fight where they need it to be. The example of Robbie Lawler can be extended to the fight against Carlos Condit, and a more contemporary instance could be Calvin Kattar (who’s as elite as they come in the pocket, but struggles against an opponent with the length and outside-footwork to deny the pocket completely). A truly limited fighter doesn’t just have a narrow area of advantage, because most good fighters have a place they want the fight to be; the second criterion is that a limited fighter can’t access that area unless their opponent consents to it.

This is where Cody Garbrandt lies. In even exchanges, “No Love” is as advertised; his swift ascendancy through the ranks showed that, as until his fight for the belt, the danger he posed in exchanges on even-ground left him so spectacularly dangerous that no man could beat him on the come-up. After a dazzling performance against Dominick Cruz to take the title, though, the limits began to show, not just in terms of Garbrandt’s often (and rightly) maligned decision-making, but more instructively in the fundamental construction of his skillset.

A Meteoric Rise

A product of Calfornia’s Team Alpha Male, Garbrandt’s undefeated run was not a subtle one; from his first fight in the UFC, he was earmarked as a star, and his camp-affiliation was a solid one for a fighter with a boxing base (as Urijah Faber's collective rarely fails to develop passable defensive-wrestlers, and Garbrandt’s own wrestling background only contributed to that). Garbrandt’s debut was the longest fight of his career until that point, as he’d only gone about 30 seconds into the second frame before his longest pre-UFC bout ended, and the snakebitten Marcus Brimage took him just over fourteen minutes. In the context of someone who fought for the 135 belt five fights later, Brimage was a very odd performance from Garbrandt; if anything, it seemed more like a fight signifying that Garbrandt had a long way to go to contend against the more dangerous fighters in the division. However, what made the difference in that bout was what always makes the difference for Cody, and that is his edge in the even-exchange.

Early in the fight, Brimage looking to close distance was troubled by Garbrandt’s signature counter-combinations; while Garbrandt’s punch selection is narrow (more on that later), just the idea of countering with more than one punch at a time is a pretty huge advantage over the vast majority of boxers in MMA. Against the southpaw Brimage, the combo was the 2-3; Garbrandt could run Brimage into the straight through the open side, and then follow up with the left hook as Brimage exited. The insane handspeed of “No Love” helped there too.

However, Brimage figured that out nicely, and his solution was to feint his way in. This worked in a couple ways; one, he could draw the combination out of Garbrandt and come in low to punish it….

…and two, he could cover his entries and land before Garbrandt realized that Brimage wasn’t just feinting this time. Absolutely classic stuff in terms of fundamental boxing.

Overall, Brimage had a bizarre amount of success (considering Garbrandt’s well-known amateur boxing background) just swinging with Cody when he punched. Brimage wasn’t the defensive operator to make him miss consistently, but when he bit down and swung on the counter, Cody just ate it fairly often. This goes to the heart of Garbrandt’s greatest issue, which is that his offense doesn’t come with defense; essentially, he’s open on the counter all the time. This will become clearer as his career develops.

Garbrandt’s central advantage, however, showed when Brimage conceded to even trades; when he didn’t pull out Garbrandt’s counter or make him hesitant, or he lingered too long in the pocket, he couldn’t get out of the way of Garbrandt’s insanity. The important thing to note here is this: even in his winning performances where he isn’t throwing the fight away, Garbrandt is not a particularly diverse puncher or a defensively-responsible fighter. Even as he was squared against the fence, Garbrandt committed to swinging and not resetting to get his stance back; Garbrandt will concede any disadvantage to stay in the pocket with his man, because he trusts that he’s fast enough and powerful enough to bomb them anyway, and usually, it’s true. Brimage could land on Cody in the exchanges, but when Cody got his bearings, he just landed two or three harder ones in a fraction of the time, and Brimage couldn’t take it by the end.

This was not a consistent performance by Garbrandt in the slightest; however, that is part of his appeal as a bantamweight, that he doesn’t need the consistency that others do. Garbrandt’s need for a sustained technical edge is lessened by his status as a terrific mechanical puncher for the weight-class and a fast accurate one as well. Combined with his nose for a finish, Garbrandt looked less like a contender against Brimage and more like someone who could force any of his opponents into a more conservative fight to survive against him.

Where Garbrandt started looking like an actual contender was against Thomas Almeida. At that time undefeated as a “Muay Thai” prospect with over double the professional bouts of Garbrandt, Almeida’s wild offensive breadth belied a reasonably deep skillset in the pocket. Like Garbrandt, Almeida was a terrific finisher, but more of a swarming volume threat than the pure-counterpuncher Garbrandt was against Brimage; this made for an interesting style matchup, of Garbrandt needing to cut the buzzsaw off at the pass before he could really get going with his flurries. It was essentially a fight to see which of the two great prospects deserved consideration as a contender, and given Garbrandt’s massive push to the title scene after that, it’s hard to see the promotion being unhappy with the result; Garbrandt razed the seventh-ranked Almeida to stake his claim to being elite.

It’s worth mentioning how incredibly nascent Garbrandt was for the Brimage bout, and that was clear in the bout with Almeida, where he had a bit more experience and seemed to have a much better idea of what he wanted. Almeida’s porous defense against a bigger tighter puncher (which was also present against Brad Pickett) reared its head as Garbrandt threw his massive hooking leads. and the fast start of Garbrandt posed a different problem to Almeida, who generally needed to be woken up a bit in a fight. Garbrandt hunted Almeida down before Thominhas could get into a rhythm.

As before, every time Almeida twitched, Garbrandt was on a hair-trigger on the counter with his combinations. Also as before, Garbrandt landed more shots and better shots in even-exchanges; however, Almeida just needed the composure to swing back to land himself.

Fig. 1

Garbrandt’s greater urgency against Almeida was facilitated by a few things, both found in the finish and also in an earlier flurry that hurt the Brazilian. The first was the way Garbrandt shifted, which both served his combination-punching and his desire to get Almeida to the fence; Garbrandt would throw his right hand and leap to an outside-angle as he shifted, and this would both cut off Almeida’s exit to Garbrandt’s right and shorten Garbrandt’s left hand. The shift is done somewhat clumsily, he’s squared-up instead of going fully to southpaw, but the concept is there to take that angle. (Fig. 1)

The second was doubling on his left hand, which changed the rhythm of his flurries and also served to pressure. The first part was more clear when he hurt Almeida and doubled on the left hook against the fence, which caught Almeida completely unaware, but the second part was how he got Almeida to the fence for the finish. Garbrandt’s shift meant that there was a single route off the fence and away from Garbrandt for a hurt Almeida, towards Garbrandt’s left hand; Garbrandt stepping back to orthodox to throw a second left hook forced Almeida back straight to the fence, and teed up a monster of a right from Cody that took Almeida’s 0.

In tone, Garbrandt’s fight against Almeida couldn’t have been more different from the fight against Brimage; Brimage got all the room to hang himself and then some, where Almeida couldn’t get a breath when Garbrandt wanted to push him back. Cody still wasn’t defensively the best (or even particularly notable), but he fought a smart strategic fight against an opponent who couldn’t endure being forced into boxing-exchanges over and over. Tactically, there were a few new tools, tools that would appear again in Garbrandt’s title effort, and which seemed to suggest that Garbrandt’s days as a reckless left-righter were over. Dominick Cruz awaited.

The Chosen One

There are very valid questions to be asked regarding the nature of Cody Garbrandt’s title opportunity in December 2016, which was a product of Garbrandt’s marketability as a knockout artist (especially after smoking Takeya Mizugaki in under a minute) and the famed feud between Garbrandt’s team and the champion. In fact, the two men with purely-merit claims to a title fight had clashed in July of that year; the former champion, TJ Dillashaw, returned from a razorclose title loss to defeat Raphael Assuncao at UFC 200. However, Dillashaw then turned around to face another contender; the stone hands of John Lineker were next for Dillashaw, on the same card as Garbrandt’s shot at Dominick Cruz. All the title-eliminator did was ensure that Garbrandt was only passing over one man and not two, with the side effect of knocking one of the promotion’s most longstanding inconveniences in Assuncao (on nearly every axis the exact opposite of Garbrandt, a tremendously proven and crafty and tough veteran with the marketability of a cactus) back down the rankings.

The injustice of #1 (off a top-ranked win) facing #2 on the same card as #5 facing the champion aside, Garbrandt seemed to prove that he was a true elite with his performance at UFC 207. Cruz was inscrutable for much of his title reign, with Joseph Benavidez and Dillashaw finding cracks (enough so to arguably deserve the decision over him) but never enough to blow his system to pieces; with “No Love”, however, it seemed like Team Alpha Male had molded a fighter from the ground up to batter the man at 135.

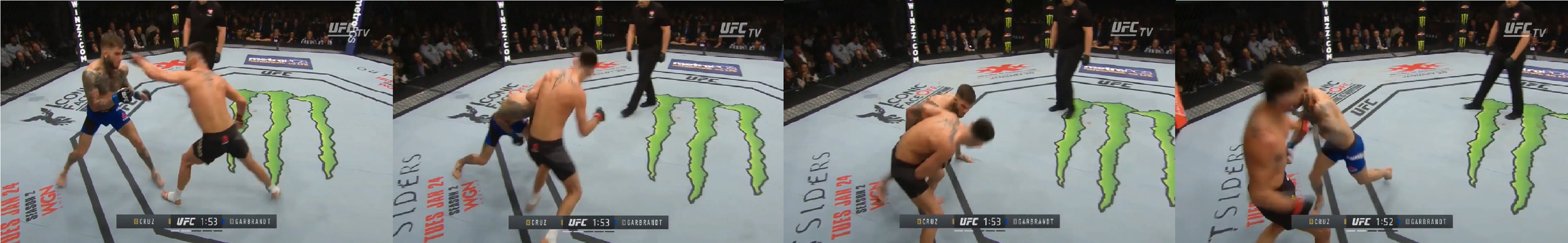

Broadly, the Cruz fight was far more similar to the Brimage gameplan for Garbrandt than the Almeida one; as seen later, Garbrandt did pursue Cruz, but it was largely an extension of his counterpunching. He didn’t hunt Cruz down, he made Cruz lead himself, and looked to rack up points from the outside with a bare-bones kicking game that encouraged Cruz to close him down.

The problem for Cruz was that the mechanics of that closing-down needed to be far tighter than they were. Compared to Garbrandt’s mechanically-strong punching and his absurd speed, Cruz was crafty but loose, and the craft didn’t make up the difference. This manifested in Garbrandt’s defensive movement (which was good when he wasn’t trying to counter, he could roll under Cruz’s ugly straight-armed shots and break the line of Cruz’s flurries with his pivot)…

…and in terms of the even-exchange, where Cruz was both hopelessly outgunned and completely out-positioned by an opponent who simply remained in his stance. Garbrandt looked for things like cross-counters as Cruz entered, but so much of the dynamic was simply Cruz’s feet not being equipped to deal with pocket-exchanges, and Garbrandt’s punches being tighter and sharper. That said, again we see Garbrandt’s flaws come to bear; Garbrandt is landing more, he’s landing harder, but when he commits to landing as Cruz swings, he’s invariably in the way of it too. Garbrandt’s head is stock-still, he doesn’t even care about the shots coming back at him (and fair play, as Cruz is not built as a power-puncher), he’s just happy to be in a range where he can trade.

What made this fight nightmarish for Cruz was how Garbrandt could track his exits. A lot of Cruz is angling in and out, and that’s smart against a fighter looking to catch him on the counter, but Cruz’s form here is also a bit ugly; as Cruz circled or darted past Garbrandt, Garbrandt could pivot or shift through his combination to track him, and catch him leaving. When Cruz tried to play the angular game to keep the buzzsaw turning, he found that it turned on a shorter axis, and left him the one running.

Fig. 2

For example, the first clip (Fig. 2) shows Cruz looking to angle into the open side after throwing his jab; however, Garbrandt simply pivots off his lead foot to step into southpaw. This leaves Cruz trapped within Garbrandt’s stance, since Garbrandt had taken the outside-angle at the same time, and that blocked off the direction into which Cruz was moving (to Garbrandt’s right), and Cody had his rear left hand ready to go as Cruz was stuck in place.

The final important component of that was Garbrandt’s takedown defense and scrambling, against a truly brilliant takedown-artist in Cruz. This is why most fighters couldn’t simply exchange with Cruz even if they had him pinned down, because if they did, the reactive takedown would’ve stopped them in their tracks and made them hesitate to try again. Instead, Garbrandt just scrambled his heart out, and it left Cruz’s option to shoot underneath the hard-charging Garbrandt a waste of time.

It was a terrific performance by Garbrandt, one that confirmed all the faith that his team had put into him, and all the machinations that the UFC had pursued to get him to the top. Beating Cruz made it seem to be clear that he would’ve gotten there anyway; no one had been able to touch Cruz for a good deal of his reign, TJ Dillashaw couldn’t beat him off a historic injury layoff, and Garbrandt blew him out of the water when the champion was as active as he had ever been. He was undefeated, he was marketable, he was flashy, and now he was tested against the very best, so the Garbrandt era had begun.

A Meteor’s Fate

After the Cruz fight, Garbrandt seemed to be headed nowhere but up; beating the longstanding bantamweight king from pillar to post took Garbrandt from a potential hypejob to the real deal very quickly, and his next fight was one where he was favored fairly heavily on the books. His opponent was the aforementioned TJ Dillashaw, who had wrecked John Lineker to cement himself as the top contender at UFC 207. Garbrandt’s title victory left a built-in storyline for the fight; not only did Dillashaw join the great Duane “Bang” Ludwig after a split with Garbrandt’s own team, his diverse team of specialists was a philosophical contrast to Garbrandt’s insistence upon loyalty to Alpha Male above all else.

While the details of the feud between Dillashaw and TAM remain ambiguous (and irrelevant), the ultimate results of Dillashaw’s defection were extraordinary. The two-fight series between Dillashaw and Garbrandt made abundantly clear who the better fighter was; more pointedly, it made clear who was better-coached, as the rematch saw Garbrandt become the stage for the ronin’s magnum opus.

Really from the beginning of the series, Dillashaw had a good idea of how to deal with Garbrandt, even if he couldn’t parlay that into early success. What to pay attention to with Dillashaw, as opposed to Garbrandt, is how he’s initiating the exchange while taking defensive maneuvers; Dillashaw would punch a bit and immediately drop a level, even when Garbrandt’s shots didn’t come. In other words, he wasn’t reacting to Cody, because Cody’s simply too fast to deal with reactively; rather, he was proactive in getting himself out of the way of the counter-combinations he expected from Garbrandt.

Fig. 3

The third clip (Fig. 3) might be the most instructive. Dillashaw’s in southpaw and throws a pawing straight left, and it’s obvious that he’s just testing out the trigger on Garbrandt’s counters; it wasn’t a shot he sat down on, he just left the straight extended, and waited for Garbrandt to swing back. Garbrandt reacted with his trusty 2-3, which Dillashaw had already weaved underneath to come up with a right hook from southpaw. It didn’t quite land clean, more as a cuffing shot, and Dillashaw knew that Garbrandt would be barrelling after him shortly, so he turned the missed hook into a double-collar tie, and contained the rush. Dillashaw didn’t relinquish control of this exchange for a second, and it came down to Dillashaw being able to defend shots while still being in range (which is where the great Cruz’s game failed him).

The end of round 1 showed why he had to do all that, as if there were ever any doubt. Garbrandt spent a great deal of the round waiting for entries that could find him the land he needed, and Dillashaw lurching into range after hearing the 10-second clacker is what it took. Dillashaw strode into the pocket upright with no trap set, even as Garbrandt hadn’t bitten on the feint beforehand, and paid for it. Garbrandt in an exchange with no pretenses was still extremely potent.

After that slip-up, Dillashaw seemed a bit warier of entering the pocket at all, which was justified (if not necessarily good). Duane Ludwig had advised him to sit on the outside and kick, and while Garbrandt had found some success running Dillashaw down the center as he kicked, he didn’t have a consistent way of dealing with them at range; Dillashaw varying the level of his kicking offense eventually got through, and resulted in a knockdown for Dillashaw.

For a boxer, the end of the fight was the most concerning part, because the finish saw a very worrying thing from “No Love”. It was seen in the Brimage fight how willing Garbrandt was to swing even at a positional disadvantage (such as when he was squared against the fence); that reared its head again in Dillashaw I. A southpaw Dillashaw feints a jab and steps to an outside angle, but it isn’t particularly subtle; at first, it looks like Garbrandt is trying to pull off Raphael Assuncao’s inside-angle pivot, which is how Assuncao dealt with Dillashaw when he found his advantage in open-stance. However, Garbrandt was actually just turning to face, and square up to swing wildly as soon as he saw Dillashaw move; it wasn’t a smart repositioning, nor a reset, and Dillashaw knew that. Dillashaw was in stance and Garbrandt was squared up, and Dillashaw knew what was coming, so he cracked Garbrandt with a southpaw right-hook to finish his undefeated tenure.

The rematch was essentially just a distillation of the first fight, in which Dillashaw (an absolutely monstrous rematch-fighter) built on how successful his proactive defensive measures were the first time. This time, he countered more actively off them, knowing that Garbrandt’s arsenal didn’t include something like an uppercut, so he could just look to duck the right hand every time Garbrandt twitched. In fact, Dillashaw used the fight to try out a shoulder-roll, which he didn’t really do before, which speaks to his confidence in both the timing and the trajectory of Garbrandt’s rear-hand. This led to the exchange that has come to define the fall of Garbrandt, in which Dillashaw threw the same counter thrice in a row to drop “No Love”, and the finish came off the same difference in defensive-awareness.

The swift dismantling made clear that any adjustments that Garbrandt made were nonexistent, or at least irrelevant. The commentary seemed to think his kicking game was one, but Garbrandt had always been an active kicker, back to the Brimage fight; insofar as what got him knocked out, Garbrandt did not adjust to deal with it.

The rematch stands as one of the most uselessly predatory instances of matchmaking one can find in recent MMA; before the fight, Dillashaw claimed he’d end Garbrandt’s career, and there’s a case to be made that the door was shut on Garbrandt’s elite tenure as soon as Dillashaw easily tore him apart at UFC 227. It was a desperation move from the UFC, clinging to Garbrandt’s sole knockdown, and yet the rematch took Garbrandt’s “almost won, close fight” and exposed it as an anomaly in a fight where the participants were as far apart in skill as they possibly could be. When Garbrandt didn’t get exchanges on his terms, he wasn’t the man anymore, and Dillashaw gave him no exchanges like that. When both men are playing the exchange-game to outwill the other, Garbrandt is hard to beat, but a bit of tact from Dillashaw and the danger was largely gone.

In response to the loss, the UFC gave Garbrandt what many believed to be a sizable step back at UFC 235, in the quietly surging Pedro Munhoz; the durable grappler had been gaining some comfort as a body-kicker with a heavy left hook, but the speed differential was the talking point going into the bout. John Dodson had exploited Munhoz’s somewhat lumbering nature quite easily, and Garbrandt was expected to have similar success. How it turned out was a bit different, as the issues Garbrandt showed against Dillashaw manifested once again.

Even without the distinct angular-blitzing footwork of TJ Dillashaw, Pedro Munhoz fought a genuinely shrewd fight against Cody Garbrandt. Defensively, Munhoz is largely just a shell, but Garbrandt wasn’t the kind to rip it apart the way someone like Jimmie Rivera did; Garbrandt’s wide-swings largely landed on Munhoz’s arms through the early going, and Garbrandt did nothing to change it. What Munhoz did was kick at the legs of Garbrandt, and his kicks were hard enough (and often aimed low) to knock Garbrandt’s stance out; this took away the threat of Garbrandt countering by just blitzing up the middle, the way he did against Augusto Mendes and at times against Dillashaw and Cruz.

The second part was the right-hand counter as Garbrandt blitzed in, and this worked because (for all his rawness as a boxer) Munhoz understood well what Garbrandt was going to try every time he committed. Like Dillashaw, Munhoz just ducked to throw the counter, and it worked. Garbrandt’s uprightness in the pocket got him a not-so-cheeky nodder for the knockdown, as Munhoz entered off the kick and looked for a left hook but his head beat his fist to the target.

This exchange again goes to the heart of the criticism in this article, and explains why Garbrandt can look like a defensive savant at times and other times look…enthusiastically not so. When Garbrandt is looking to catch Munhoz coming in, he’s in offense mode; his chin is up and he’s swinging hard, and he eats Munhoz’s overhand. When that misses, Garbrandt turns on defense mode, and weaves quite smoothly underneath what Munhoz is looking to follow up with. It’s offense, or it’s defense, and the strongest boxers in MMA can do both simultaneously (even if it’s not a function of comfort, at least as a function of training); for Cody, his vulnerability on the counter hasn’t been bred out of him.

The final exchange in all its glory. Garbrandt again goes on offense after the knockdown, and it’s again the reliance on his aggression bailing him out, as he’s not really varying his offense with his hands (although he did land a knee as he grabbed a clinch as Munhoz ducked, which was nice). There are very few defensive measures taken here by Garbrandt, as Munhoz is consistently lowering his level as he swings, and that makes the difference. Garbrandt was certainly acting imprudent here, chasing Munhoz around the cage, but there are ways to do that while mitigating the returns of a fairly limited boxer; the problem is that Garbrandt just isn’t that good at doing it that way.

Concluding Thoughts

The more popular notion of Garbrandt being an underachiever isn’t wrong; a fighter with his athleticism and offensive-potency could’ve become something truly special, instead of ending up a flash in the pan. Garbrandt has become a cautionary tale in multiple respects, one of rocketing prospects quickly and of not matching them up carefully, and of the danger of fierce camp loyalty when that camp couldn’t ever really give him depth in the area he needed it the most. Had Garbrandt come up more sensibly through a tougher field of fighters, he may have failed before he even got to Cruz; however, he also may have ironed out the issues he had against Dillashaw and Munhoz before he encountered them for the first time against elite fighters. It truly didn’t matter who consented to the wild-exchange with Garbrandt, whether it was his introduction to the UFC or the cream-of-the-crop, all came out worse for wear, but forcing his opponent to consent to outwilling and outpunching (rather than outsmarting) him was a fool’s errand.

There’s also a case, though, that Garbrandt’s career should be framed as an overachievement; the expectations placed upon him throughout his career were tremendous for a prospect from the very beginning, from his team as the fated Cruz-killer, from the promotion as their money-maker, and from the public as a future elite. For a brief shining moment, he found a way to live up to all of them, as the Cruz performance remains one of the best title-winning efforts ever, over a fighter who’s arguably a top-ten greatest ever. While Cruz’s subsequent three-year period of inactivity and summary loss to Henry Cejudo diminished the win a bit, UFC 207 stands as the stage for one of the most surprising events in MMA, as the complexity of the champion was reduced by the challenger to a couple nodes where he had the edge. There’s a very compelling case for framing Garbrandt as Team Alpha Male’s single-context weapon to deal with their greatest foil, and in that sense, Garbrandt was as successful as anyone; the traits that allowed him to defeat an incredibly unique champion in Dominick Cruz didn’t transfer to defeating challenges that he wasn’t designed to face, but one could consider that irrelevant to a machine that was tuned to topple the king and the king alone.

Garbrandt is scheduled next to face Raphael Assuncao, the aging bantamweight great who arguably should’ve contended for the title years ago (in the stead of Garbrandt himself). On paper, given all the tendencies Garbrandt’s shown, it’s fairly nightmarish; Assuncao’s a solid kicker, he’s extremely diligent about his positioning in the pocket, and his trademark is a versatile and powerful right-hand counter. If he were in his prime, it would be difficult to find a route to victory for “No Love”. However, Garbrandt’s certainly surprised before, and this might be another time where his hands are faster than his head is slow.