Introduction to Lethwei

Lethwei comes from the Burmese "Myanma Yoeyar Letwhae", which means "Myanmar Traditional Boxing". In Burmese language the "t" is silent in this case and is pronounced La-way. In Myanmar, lethwei is referred to as Traditional Boxing. If you leave out the Traditional part, you may end up asking for western gloved boxing.

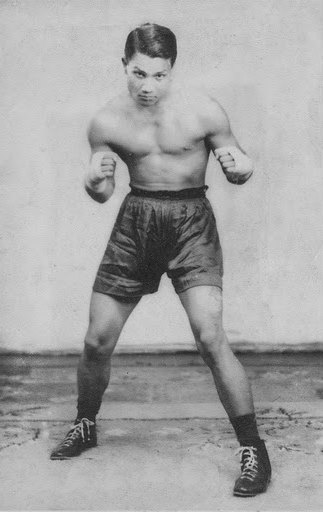

1968, Courtesy of Taw Win Yoe Yar

The sport is also referred to as Burmese bare-knuckle boxing. Although no longer true in present times, boxers traditionally did not wear wraps as it was a means of self-defense in times of conflict. Lethwei from that time was much more barbaric as even groin strikes were a legal means of winning and the motto was simply to protect yourself at all times. Fights could last for hours on end. It wasn't until the 50s and 60s that wraps were starting to be used more often than not.

Pinpointing important events in history is difficult, it is believed Lethwei initially started forming roughly a thousand years ago during the rise of the Pagan Kingdom. It is part of the umbrella term ‘Thaing’ used to describe all the fighting arts in Myanmar, from wrestling to sword fighting. A term that carries with it a rich and somewhat violent history, it was created at approximately the same time. Although violent in nature, the kindheartedness in lethwei, and of course Thaing as a whole, has it's roots in Buddhism. Being respectful to others is almost more natural than the fighting art itself. You will not see people talk bad of one another, lending a helping hand whenever possible. Inappropriate and unjust manners do not belong inside the ring it whatever form.

Lethwei is a type of Bando which can be seen as a milder system of unarmed combat. Bando's roots precede that of lethwei and was influenced and developed over time by coming into contact with neighboring merchants, diplomats and travelers during the Pyu millennium. It was the initial combat sport of the Pyu people at that time.

As early as the 11th century during King Anawrahta Min Saw's reign, monks were using and teaching this type of Bando now known as lethwei. They taught military personnel but also noblemen and princes. For centuries fights were held at Buddhist festivals sometimes at the patronage of the reigning King. Notable and skilled boxers were honoured by having their names engraved on palace walls and were allowed to call themselves royal boxers. Lethwei at that time was also known as the sport of Kings.

During its centuries of conflict up until the 19th century, lethwei was a means of unarmed combat and in leisure times mostly practiced by the military and defenders of the Kingdom. During the British rule from 1824-1948 and World War II, Thaing, and consequently lethwei, suffered near extinction as it was forbidden and only used as entertainment for British soldiers and wealthy high-class purveyors. The ancient combat sport was performed in secret and was kept alive in faraway villages and in times thereafter mostly practiced by farmers and peasants. Matches are held during religious pagoda festivals, funerals and other Buddhistic practices during harvest time. In those areas this remains somewhat the same to this day.

Kyar Ba Nyein

“ “Tiger” was born to a Muslim family in Mandalay in 1923, when the country was under British colonial rule. He learned Western boxing from a young age and won his first national trophy at the age of 13.” - MyanmarMix

Unlike the sport of Kings it once was, it was now reduced to a poor man's activity and deemed archaic. Many people are responsible for the rise and renewed interest in the various Myanmar martial arts. Thanks to the efforts of Kyar Ba Nyein, a boxer from Mandalay born in 1923, lethwei saw a revival. From 1954 onward he set out to draw up new rules and regulations for the sport in order to drag it out of its present unfashionable state. He traveled to the southern villages to find boxers and to accumulate data and wisdom from the old masters that still taught the old sport. With new rules in place he brought the boxers to the big city to perform and also showcased it in neighboring countries.

Although the current state of lethwei today is riding on Ba Nyein’s coattails, he did not live to see the resurgence of the sport. But his contribution by establishing a strong framework that formed the basis of regulated lethwei was immense and although he sought to bring renewed popularity to the sport, there was one barrier he could not overcome.

As industrious as he was trying to bring back a dying art, as quickly his efforts were shot down by what would turn out to be one of the longest running military dictatorships the world had seen.

In the 1962 coup d'état the military took control of the government and placed the country in isolation. It was during this military dictatorship in 1988 that State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi rose to prominence. The nationwide protests and her political success were ignored by the military junta and the country remained closed to the world until 2011. Since the 2010 general elections there has been a gradual change in the political landscape, in part attributed to the efforts of Aung San Suu Kyi. This change eventually made it easier for foreigners to enter the country without the hassle and paranoia from before.

Because the country was now “open” to foreign fighters and investors, it also created a sudden opportunity to capitalize on something the majority of the world had not yet experienced. Something that was until recently enjoyed in the countryside for entertainment of locals and done in celebration during festivals is now the spotlight of the entire globe.

Copyright and courtesy of Martial Couderette. Taken from LETHWEI Myanmar Traditional Boxing.

One of the latest changes to the landscape is the founding of World Lethwei Championship (WLC) under the banner of Myanmar Lekkha Moun Co Ltd. Initially staging events under the Lekkha Moun name in 2016, it now hosts events as WLC since the start of 2017. In order to fit in to the current state of regulation and safety for combat sports around the world, the company adopted a set of rules that were previously used in 1996 for the inaugural Golden Belt Championship. This meant that the two-minute recovery timeout was removed and that judges were now ringside to score the fight to prevent the outcome of a draw.

Much like Ba Nyein in the 50’s, WLC has “changed” the rules in order to further develop and popularize the ancient sport. These changes created some tension between the traditionalists and supporters of the new rules. It is no secret that the International Lethwei Federation Japan which hosts lethwei events in Japan under traditional rules does not support WLC’s ideology. Like a fashion industry of its own, most combat sports continue to evolve and change. In a world where vale tudo and no holds barred fights were once popular, people had begun to make changes to make these sports safer. Yet at the same time more and more places on earth are embracing a change of scenery with the renewed interest in bare-knuckle boxing and the discovery of lethwei. Whether the ever changing sport and the interest in it will eventually benefit it in the long term remains to be seen.

This extremely short introduction will show similarities with published work by Vincent Giordano, Zoran Rebac, Martial Couderette and Myanmar Times. I’ve done most of this by memory but I cannot stress enough the influence these three people in particular have had on me by teaching me the things I know now. As the sport grows it’s of importance to keep acknowledging and thanking those that worked tirelessly for years to help open doors and minds of individuals like me (and you).